Voice acting is as ubiquitous as loot gathering in RPGs today. With a few exceptions, every character in modern RPGs has a voice. The reason for this is because in addition to the visual upgrades that every game has received over the years, the move towards cinematic presentation has made voice acting a necessity.

If Dragon Age is any example, having a mute protagonist—that is, mute in terms of the player character lacking a spoken voice—with dialogue choices serves only to detract from the immersion. There was a profound disconnect between the player character and his or her interaction with the rest of the world. In any case, that is but one example of what happens when all characters speak but the one in control of the player.

In contrast, the Mass Effect games and Dragon Age II—which suffers from problems of its own—are far more engrossing, as they allow players to literally role-play their character instead of writing on a blank canvas.

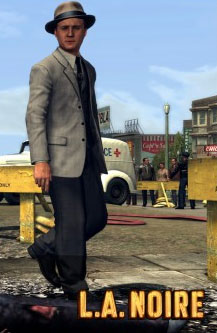

It goes without saying that dialogue is essential to RPGs, and although modern RPGs may lack sophisticated mechanical choices—having many dialogue options to choose from—they can make up for it by allowing the player to role-play a certain character, albeit in a limited, but more enriched form. Consider the personality of Hawke in Dragon Age 2, whose ability to be aggressive, righteous, or even snarky allows the player to fill a certain role without coming across as schizophrenic. L.A. Noire’s poorly executed dialogue system portrayed the game’s protagonist Cole Phelps as insane, but only when the player selected the wrong answers.

It is true the player is allowed fewer choices, but the choices he or she makes can have a greater impact on the narrative should the game’s writers invest a significant amount of personality into the protagonist, who serves as more than the tabula rasa, or blank slates, of RPGs past.

Additionally, choices need not be constrained by dialogue alone, as game developers can find ways to augment interactivity by allowing the player—through core or ancillary mechanics and systems—to play the game as they would like. RPGs need not be fixed on rails.

As more and more games borrow elements from the RPG genre through the inclusion of experience points, levels, and item accumulation, so too should RPGs borrow the interactive elements of first and third person shooters and the hack-and-slash genres. There’s just no good argument for retaining the dice-rolling and statistics-heavy gameplay mechanics of pen and paper RPGs from which computer RPGs derived. Computer RPGs, like every other videogame genre, must embrace its medium instead of emulating another.

In summation, voice acting, like visuals and interactive gameplay mechanics, are what define computer RPGs and set them apart from their predecessors on the kitchen table.

Injustice: Gods Among Us Review

Injustice: Gods Among Us Review Review: Hotline Miami 2

Review: Hotline Miami 2 Three Things at E3 That Need to Stop, Part 3: Quit Perpetuating a Legitimately Evil Empire

Three Things at E3 That Need to Stop, Part 3: Quit Perpetuating a Legitimately Evil Empire Top 10 iPhone 5 Games of 2013

Top 10 iPhone 5 Games of 2013 Sequence 3 - Somewhere That's Green: Assassin's Creed: Syndicate Walkthrough

Sequence 3 - Somewhere That's Green: Assassin's Creed: Syndicate Walkthrough