As an undergraduate at UCLA I had the privilege of taking a science fiction class with none other than N. Katherine Hayles, author of a bunch of books you may have heard of and altogether one of the sharpest women I've ever had the honor to know. One of the pearls of wisdom she imparted, of which there were many, was that professional science fiction authors despised the term "sci-fi." 2001 is science fiction. Halo is sci-fi. I wouldn't even know what to qualify Star Wars as—maybe science fantasy? (I'd call it a space opera, Ed.)

Along this spectrum that Hayles set up for her wide-eyed students, BioWare's Mass Effect franchise definitely lands in sci-fi territory. It's fluffy with a dash of math, just like Star Trek when it isn't getting its physics and terminology utterly wrong. (It pays to keep in mind that Star Trek, at least as far as Next Generation, knows what a parsec is. Star Wars will never be able to make that claim.) So even though it has that Star Wars sense of the epic scale and space-age mysticism, it's really more of a Star Trek setting, all naval politics with a hefty helping of marine badassery and other ostentatious displays of one's virility.

It's also a bit aesthetically retro, something I find best expressed in its city designs. The Stanford torus of the Citadel Presidium, the converted mining facility of Omega. It's somewhere between Clarke and Steakley—that is, somewhere between golden age visionary and mulched up, recycled B-movie pot-boiler. It throws a bit of hard SF or speculative science (quantum entanglement, etc) in there just often enough that I'm willing to forgive its flimsier bits (the traditional conceits of artificial gravity, the anthropomorphic aliens) and go along for the ride again and again and again.

But the real aspect to Mass Effect which makes me love it even though Star Trek and Star Wars both offer longer histories, larger mythologies and bigger (more inclusive) fandoms, is the subtle critiques it offers on contemporary problems.

As another professor of mine would later note, eventually these big franchises just end up becoming self-referential. The image of Star Trek as a sterilized, Western-normative utopia may have spoken at one point to various aspirations and hopes for then-Cold War-era humanity but by and large it's quite disconnected from contemporary trajectories in culture and politics (blame studio meddling if you wish). As for Star Wars, well, it is quite explicitly a story from long ago and far, far away. It may hold up a mirror to the contemporary world (or at least Lucas's vanity) but it can't do so very blatantly. That is why I tend to treat it as a fantasy rather than sci-fi story. It reflects a premodern episteme (Thank Foucault for this term, Ed.) not wholly reflective of our modern-day condition. The fact that it's originally based on Kurosawa's image of feudal Japan only underscores this.

Pictured: "Leia, Han, R2D2 and C3PO: the first draft.

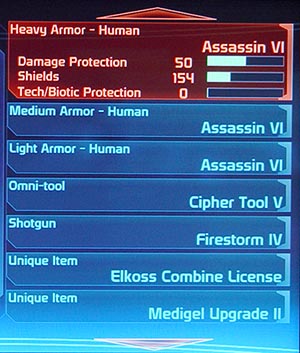

Mass Effect is neither the far future nor a fantastic alternate history. It's the near future and it projects current situations into a hypothetical future context, namely: branding, corporatization, commodity culture, cosmetic surgery and the military industrial complex. Your ship quartermaster can't sell items to you unless you buy him the right licenses from manufacturers—all war profiteers, who sell their armor and weapons to armies and private militias both. Despite being part of a unified human military, there is a distinct impression in this game that you're but one strong-arm in a galaxy full of competing mercenaries. That you spend the second game on the payroll of a human-chauvinist private enterprise and effectively become part of its corporate structure only further drives home this idea.

But I like the licenses in the first game best for delivering this idea: not only is dog-eat-dog capitalism the name of the game in Mass Effect's story setting, it's also a game mechanic. This metaphor becomes slightly more abstracted with all the resource mining and other entrepreneurial activities you're able to take on. In a lot of resource management games, after all, you collect resources just because they're there. Because you need to construct additional pylons. Because you need to afford the next hull refit.

In Mass Effect, you participate in resource collection as one component of a large apparatus of galactic commerce. It took three or four play-throughs for me to actually get that a large component of Saren's corruption was not just being an evil cyborg and allying with even more evil machines, it was legitimate fiscal corruption. He wasn't just a free-agent lone gunman of a renegade Spectre, he was roughly the equivalent of a Wall Street executive. The notion that a plot point for the first game hinges on the big bad's investment portfolio blows my mind.

In Mass Effect, you participate in resource collection as one component of a large apparatus of galactic commerce. It took three or four play-throughs for me to actually get that a large component of Saren's corruption was not just being an evil cyborg and allying with even more evil machines, it was legitimate fiscal corruption. He wasn't just a free-agent lone gunman of a renegade Spectre, he was roughly the equivalent of a Wall Street executive. The notion that a plot point for the first game hinges on the big bad's investment portfolio blows my mind.

Mass Effect also offers a few interesting treatises on race politics from the perspective of the guilty hegemonic few, but I feel these narratives are too easily muddled and missed by players to be truly effective. Which is exactly the problem of addressing these issues from the perspective of the privileged. Nowhere in the first Mass Effect is anyone asking the krogan for their opinion of their own self-determination. Contrast all this stiff political discussion to Dragon Age: Origins (same studio, different team), where you have the option of being placed directly in the shoes of the oppressed, the subjugated, the victims of a hauntingly realistic rape culture, and see the difference I'm talking about here. One problematizes, the other empathizes. One tries to sequester the problem until it can be safely ignored, the other confronts you with it.

(I would say that on the whole, however, Mass Effect makes some not-insignificant gestures toward inclusion among human races. It addresses accommodating differing religious and cultural traditions for servicepeople, for instance, and frequently features NPCs of color. But it could still go a whole hell of a lot further.)

Inasmuch as Mass Effect is a well-pummeled dead horse in game criticism, I don't think we've spent adequate time discussing what makes it a relevant narrative universe, such that Bleszinski feels prompted to call it "the Star Wars of our generation". I can reply with confidence that, no, Star Wars is the Star Wars of our generation, thanks to the franchise's utter saturation of the market from our adolescence to the present. But Mass Effect does seem to occupy a unique tertiary position, well-entrenched in gamer culture if not readily recognized outside of that, and I believe this is indeed due to how it is able to make a game out of hypercapitalist dystopia. We may believe we're playing for the dialogue wheels or the sex with aliens or the privilege to squirt yet another burst of manshooter jism from our controlling thumbs (sigh), but I'm convinced we're at least partly hooked thanks to how recognizably patterned after our own consumerist existence it is. It's all branding and licenses. Even when you're saving the galaxy.

List of Unlockables in Dragon Age Legends for Dragon Age II

List of Unlockables in Dragon Age Legends for Dragon Age II Dark Souls 2 Enemies Guide - Part 3

Dark Souls 2 Enemies Guide - Part 3 Are You People Insane? Addressing The Double Fine Kickstarter Controversy

Are You People Insane? Addressing The Double Fine Kickstarter Controversy Charli XCX reveals Japanese versions of Boom Clap and Break The Rules

Charli XCX reveals Japanese versions of Boom Clap and Break The Rules Sequence 9 - A Night To Remember: Assassin's Creed: Syndicate Ending

Sequence 9 - A Night To Remember: Assassin's Creed: Syndicate Ending