As of this year, the war on Afghanistan has been going on for over a decade--making it the longest standing war that the United States has been involved with. The average person living in the United States wouldn’t really know it, doesn’t really care, or can’t do anything about it.

The indifferent or helpless response makes sense. The “war on terror” makes it clear that the purpose of modern war is control--not conflict resolution. Peace isn’t on the drone’s radar. More war is. For in the “war on terror,” enemies could be anyone, anything; it has no particular enemy.

War is routinized, war is a spectacle, war is sanitized, war is surveillance.War becomes borderless. War cannot be ‘won’ in the traditional sense, it is ongoing, permanent. Security, and not defense, become the hallmark of ‘the war on terror,’ and this security redefines and violates civil rights in the name of the preservation of democracy. You’d think that the erosion of civil rights would create action, but this is where media such as games come into play.

Authentic and realistic are words that shooters like to brandish--they usually refer to the realistic graphics, the precise physics, or the spirit of the narrative told. Typically, the degree to which a title is “authentic” or “realistic” is debatable. Nonetheless, games sell themselves on their authenticity and realism--both of which became high in demand in American markets after 9/11, when war game sales blew up and the military scrambled to develop better simulations to, as the book Games of Empire puts it, “anticipate the new challenges of the war on terror.”

Games like Medal of Honor: Warfighter will go through great lengths to become an ‘authentic’ experience; the marketing often emphasizes how much they consult military experts on the depictions and mechanics of war represented. More recently, Medal of Honor has come under criticism for their decision to partner with brands who sell the actual guns represented in the game--they're not just realistic weapons, they're real, see?

Interestingly, the big draw of war games such as Call of Duty and Medal of Honor are their multiplayer modes, where players can play against other players in a perpetual war. This particular aspect of modern war games, I’d say, is actually the most “realistic” and “authentic” aspect about them. Though a match can be ‘won,’ a player can hop back into another fresh match as many times as they’d like, regardless of how many enemies or ‘wins’ one has accrued. There is no end.

The only exception is when a developer decides to pull the plug on the server that provides online play, but by that time, there will be a handful of new titles to buy--war games come out in yearly installments.

Other titles embody perpetual war on a narrative level, like Hybrid. The recently released XBLA title puts players in the middle of a global conflict thanks to the massive need of precious, rare resources. (Some cynics will be keen to draw parallels on that premise as well, but I digress.) The entire globe becomes a playing board and the more a faction wins matches, the more they are able to take control of an area. Theoretically it is possible to control the entire globe, but it’s more likely that the playing field remains contested and the war remains perpetual.

5th Cell programmed the game such that the first faction to attain 100 pieces of dark matter--which are awarded given enough dominance over an area--wins that “season” of Hybrid. The winning side is awarded an achievement and special helmet. You could say it’s like the game’s version of the “Mission Accomplished” banner, given that the war doesn’t actually end and nothing has really been won. The war must go on.

Having the game literally framed around a perpetual war that a player can supposedly ‘influence’ is a growing trend, as it allows developers to create a narratively sound reason for a multiplayer’s existence. Matches aren’t just isolated multiplayer elements that exist outside of the “actual” game--they are the game. Perpetual war also allows developers to craft mechanics with added complexity. Titles like Hybrid and MAG, after all, ask the player to consider war on a larger scale; to engage in battles that have significance and influence beyond the skirmish itself.

It should be noted that in effect these titles promise the player autonomy, as you are told that your actions matter in the world stage, but the endless war means that everyone’s actions are actually useless.

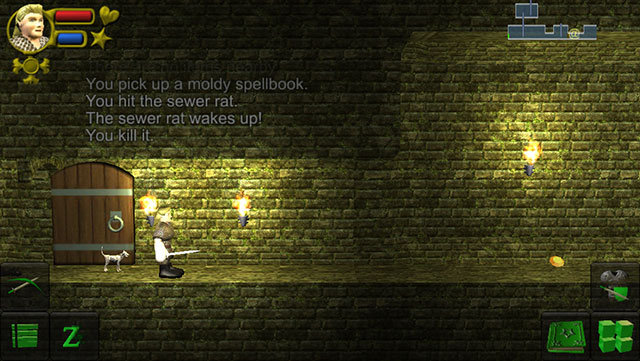

Most war games have also embraced RPG elements, which allow them to include incentives such as experience points and levels that a player accrues through daily engagement and ample playtime. One would be hard-pressed to find a title in the genre that hasn’t embraced RPG elements today.

These mechanics tap into compulsion, sure, but also relay the message that perpetual war is necessary for your development as a subject, and the means through which someone becomes empowered. Here, too, there’s an empty promise: despite how long a player might develop a character, “prestige-ing” means that the process is never-ending. You reach your level cap just to start it over again and again and again.

Naturally, war is glorified through most media, and it all works together such that the media maintains the public’s will to fight. The onslaught of war propaganda in media creates a landscape where the average person sees the idea of war as a daily reality, a given, our “normal.”

War is routinized, war is a spectacle, war is sanitized, war is surveillance.

War could even be peace, as far as the public knows--for the images we see of war in popular media are a far cry from what war actually is, making an endless war easier to maintain. After all, the war going on right now isn’t like the war conceptualize in our heads. War today is, as Robert Yang puts it, “invisible and nearly impossible to photograph. And that is a dangerous thing. So if you ever see a photo of a guy aiming a rifle, remind yourself--that’s not war....War is the US spending billions to magically airdrop and sustain a city of 45,000 people in the middle of Nowhere, Afghanistan. War is a guard tower built next to a tennis court. War doesn't take place on a battlefield...War is an unmanned drone with 96 cameras, sending back footage for 200 intelligence analysts to dissect before going home to eat pancakes. War is a cheap internet router that may or may not have fed data to Chinese intelligence agencies.”

But more importantly, if the war ends what will the player have left as entertainment?

WazHack: A Free Side-Scrolling Roguelike for iOS & Android

WazHack: A Free Side-Scrolling Roguelike for iOS & Android Fallout 4: 10 best Easter Eggs, references to films / games

Fallout 4: 10 best Easter Eggs, references to films / games Victor Vran (PC): all secret locations with maps

Victor Vran (PC): all secret locations with maps Confessions of a Back Seat Gamer: The Social Possibilities of Single Player

Confessions of a Back Seat Gamer: The Social Possibilities of Single Player Top 16 Best PC RPGs of All Time

Top 16 Best PC RPGs of All Time