In early 2012, an enterprising set of video game fans thought that the narrative of one of their preferred games didn’t make sense, so they constructed a version that did. That game was Mass Effect III, and their theory, the Indoctrination Theory, supposedly smoothed over many of the flaws in ME3’s terrible ending. “It didn’t suck, because it didn’t happen!” Unfortunately, they had the wrong game. The easiest explanation for Mass Effect III’s enraging ending was simply that it was tacked-on and add too much to the game’s mythology.

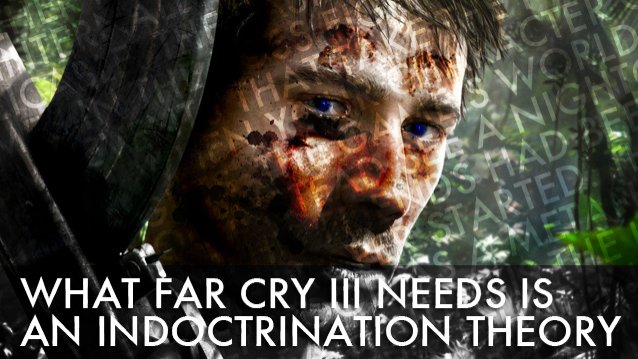

Far Cry III, moreover, needs an Indoctrination Theory. It simply doesn’t make sense. Others here at Gameranx have directly responded to the game writer’s explanation quite well, but I think it’s worth examining what made it impossible for there to be any explanation for Far Cry III’s “ludonarrative dissonance.”

The core issue: there’s a game that acts as the “real world” in Far Cry III. I don’t mean that it’s realistic, but rather, that it has a comprehensible, predictable set of rules. That’s the Far Cry III that exists outside of the story missions. When you’re controlling Jason Brody as he wanders around Rook Island, capturing outposts and upgrading your weapons and items, everything makes sense. It behaves in both an internally consistent fashion, and a fashion that’s consistent with other games within the genre. Far Cry III’s normal gameplay is that of an over-the-top first-person shooter, with nothing directly subversive happening.

On the other hand, its story missions are not internally consistent, nor are they explicable. The easiest example of this comes in the boss fights, which are quick-time events that take the form of knife fights. When your character gets into these fights, the game’s world falls away, and you instead see a nightclub that Jason and his friends had been in before the game proper started. This could be understood as a metaphor for the “dance of death” that is the knifefight, but it’s more than that. In one of the fights, Jason is stabbed, through the chest, with a large knife, but he proceeds to fight and win, with no apparent side effects. The final confrontation is even more nonsensical: you argue with the villain in his lair filled with his guards, he starts stabbing, the room changes to the dance club, you fight back, stab him, kill him...and all of the guards are also dead.

These are the same sorts of guards that you’ve been fighting and killing in the game’s “real” world. And here they’re waved away by...something. The rules are no longer true. So, when confronted with this dissonance, the player has to figure out an explanation. The easiest one is “this story is a bunch of random bullshit, who even knows what it’s supposed to mean?” Alternately, the player can remember a bunch of the game’s previous hallucinogenic moments, of which there are several, and decide that the entire game isn’t real. There’s an Indoctrination Theory to be found here, between the likely drug use of the rich Americans on vacation, the hallucinogenic drugs taken by the island’s doctor and dispensed to Brody, the hallucinogens given to Jason by the island’s warrior tribe to turn him into their avatar, and the references to the famously trippy Alice In Wonderland. Kotaku’s Kirk Hamilton has offered one solution, but I think the Jason-as-Vaas theory makes sense more as something cool the game’s developers could have done, instead of a theory of how to read the story.

These are the same sorts of guards that you’ve been fighting and killing in the game’s “real” world. And here they’re waved away by...something. The rules are no longer true.Unfortunately, Jeffrey Yoholem, the game’s writer, seems to believe there’s an option that splits the difference. It’s not that Far Cry III is supposed to be literally true, he’s arguing, nor is it that Far Cry III is all a dream. Instead, the unreality of a handful of the story missions is supposed to make the player see the whole game as a metaphor for video game colonial power fantasies.

But that can’t happen because Far Cry III isn’t balanced like that. When 97% of the game works according to certain rules, the remaining 3% are easy to dismiss as a mistake. If there had been any indication that the world of Far Cry III wasn’t what it seemed during normal gameplay, if it had ever broken its own rules and subverted player expectations in a significant fashion outside of scripted events, then the argument that Far Cry III really does subvert expectations would be justifiable. But it never actually takes the step that shows that makes the easiest reading of its theme the one that it wants. Thus an Indoctrination Theory would fit it best.

Borderlands: Transfer Saves to Handsome Collection - PS4 / Xbox One

Borderlands: Transfer Saves to Handsome Collection - PS4 / Xbox One Black Ops 2 Career and Strike Force Challenges Guide

Black Ops 2 Career and Strike Force Challenges Guide Ender of Fire (PC): Trophy guide

Ender of Fire (PC): Trophy guide Rise of the Tomb Raider Guide - How to Fast Travel

Rise of the Tomb Raider Guide - How to Fast Travel Don Bradman Cricket 14 Wiki: Everything you need to know about the game .

Don Bradman Cricket 14 Wiki: Everything you need to know about the game .