Communicating the passion, the beauty; the romance of games to non-gamers is a task that can oftentimes seem impossible. How do you explain the draw of sneaking down a corridor, slowly losing your sanity, in Amnesia? What’s so appealing about repeatedly dying and becoming frustrated with Dark Souls? Why bother to learn new and confusing button configurations to play Uncharted, when you could just pop Indiana Jones into the DVD player? How do you explain to someone why it’s fun to massacre wave upon wave of seemingly helpless bad guys?

Over the Christmas period, I tried again to get my mother into gaming; to convert her to my favourite hobby. I’ve tried before, and I’ve always failed miserably. The difference was that, this time, I was armed with Journey. It’s short, simple to play and beautiful. I was pessimistic, expecting at most an uninterested shrug after twenty minutes of aimless wandering. To my surprise, my mother took to it immediately, finishing the game three times in two days.

This highlights what I’ve long suspected about gaming: the difficulty in evangelising it has largely been down to significant shortcomings in the variety of games, and more specifically the entry level games. Entry level, or “gateway”, games are by definition very easy to play; often quite simple in concept and are well executed. Journey isn’t a magical cure-all to this problem, but the combined force of Journey and Telltale Games’ The Walking Dead are a fantastic start.

Simplicity of play is doubly important because those dipping their toes into gaming will not only be learning new button mappings, but also controller layouts and how to properly use things like analogue sticks. As a long time gamer, even I struggled the first time someone put a Wii-mote in my hand (to pre-empt cries of “noob”: I will out-waggle anyone on Wii Sports Tennis). Conversations I’ve had with the various people in my life indicate that getting used to new controls is not a problem that only I suffer from.

There is, of course, an entire genre that fits the bill of skill-based accessibility: point and click adventures.

Point and click adventures have been around for a long time, and they highlight perhaps better than any other genre the second major barrier to someone just getting into games: the conceptual barrier; sometimes referred to as gaming logic. Over the course of their existence, puzzles in games have developed their own unique style of logic, and this brand of logic can be opaque to new gamers. An experienced gamer will know the signs, will know how to search a level to begin to decode the puzzle being communicated, and will know whether or not they can push the games’ mechanics far enough to make a particular solution viable. Much of this is based on prior experience with similar games, and is not often explicitly communicated.

Game logic extends far beyond puzzles, however. Even something as simple as path-finding can be troublesome to a new gamer. My mother required fairly regular directions during her first play-through of Journey, and, on subsequent games, continually struggled with navigating her way through a particular area towards the end of Journey. If simply orientation and puzzle solving are difficult to get the hang of, it’s no wonder that new gamers struggle with optimisation in more stats-focussed RPGs and in competitive RTS games. Some genres are definitely less newbie friendly than others (here’s looking at you, FPS).

The conceptual barrier of games goes far deeper than just game logic. We’re only just beginning to see games mature and diversify the topics they discuss to include more difficult, more nuanced, themes. Beginning in a significant way with the original Bioshock, Irrational Games managed to mix a rich art style with a fantastic conceptual setting which lent itself well to the introduction of more meaningful philosophical questions. Bioshock places an emphasis on, amongst other things, the philosophy of science and epistemology; Bioshock asks what results when science, and indeed all aspects of human endeavour, go too far and break free from the restraint of ethics and morality.

Pair this with the aforementioned Journey, and we have two games that deal with the idea of discovery and exploration, but in fundamentally different ways. Bioshock asks the question from a very human perspective, whereas Journey is happy to let the player ponder without a baseline. Bioshock directs the conversation by asking difficult questions, whereas Journey is the question. Bioshock and Journey aren’t necessarily the first games to attempt this, but they are certainly amongst the more successful examples.

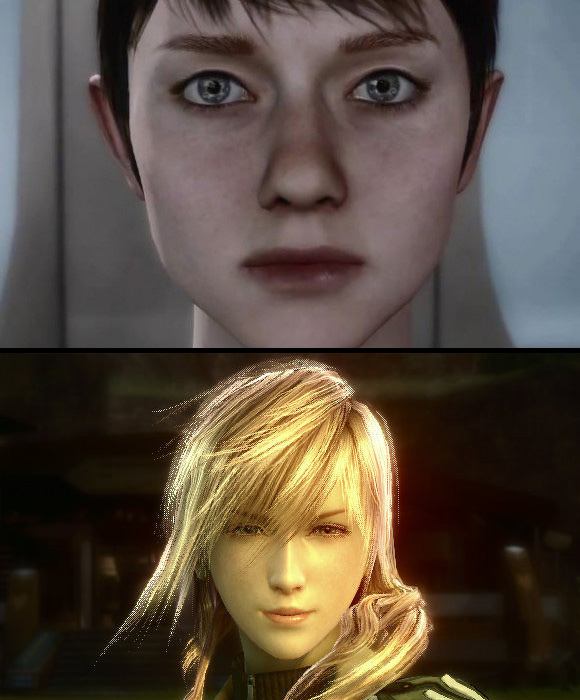

Bioshock and Journey have begun to break down the conceptual barrier, the perception, that games are ultimately shallow and thoughtless experiences. Looking at the wider array of games, there are other examples, too: Binary Domain presents questions on post humanism and L.A. Noire tells a story which is predictable, but is still much deeper than the average Rambo-esque rampage, and manages to deal with very sensitive themes along the way; Shadow of the Colossus makes you acutely aware that your heroism is an almost purely selfish endeavour and this poses a problem about the importance of perspective.

Another reputation that games have struggled to rid themselves of, is the image of an over-abundance of violence. We are bombarded with images of destruction in games. On TV, YouTube, billboards, in cinemas and on the front covers of our morning papers you will find adverts for the latest and greatest in war simulation. It’s understandable that gamers, non-gamers, and even journalists (who are expected to have a broader view of the industry), may be left with the impression that this is a hobby with an unhealthy, and possibly quite dangerous obsession.

It’s not possible to make the argument that there isn’t a lot of violence in video games: there is a lot of violence. Combat of some form or another has been, if not an essential feature, certainly a key feature of a great number of games, and even those games which don’t feature combat as part of the game-play, often depict physical confrontation at some point.

It’s worth noting that a lot of this violence, possibly even the majority of it, is in fact no more realistic than the equivalent depictions in children’s cartoons. The truly violent games - the likes of Grand Theft Auto, Mortal Kombat and Battlefield - are over-represented in advertising and in the public consciousness. This isn’t to say that violence isn’t present in video games; rather that it is only one aspect of a very diverse medium, and shouldn’t be considered to be representative of it. The distorted image of games presented in mainstream media and in advertising is only a pale imitation of what is swiftly becoming the cultural keystone of the modern age.

Parallels could be drawn between games and movies, music, or even books, but this would only distract from the real argument: that games are not purely for children. They haven’t been a children’s toy for a very long time. Just as there are movies, music and, yes, books, that aren’t appropriate for children, so are there games which are not appropriate for children. From Max Payne to Saints Row, L.A. Noire to The Witcher, some games were simply not created to be consumed by a young audience. Mature games for mature people.

“What about those gamers who describe in vivid detail and with rather too much relish, the latest brutality they inflicted on a virtual enemy”, you may ask. It’s true that some gamers can become almost disturbingly focused on the kill, particularly in games where the difficulty of killing pushes it almost to the point of being an art-form. In the majority of cases, this is likely to be a case of mistaken achievement. The gamer in question is not so much focussed on the kill, despite what they may be saying they are likely focussed on the fact that they have just overcome a very difficult challenge, and they are revelling in their success. If the kill was all they were after, they could hop into Call of Duty or Dynasty Warriors and mow down hundreds of enemies in a few hours.

Whether they are talking of that one, perfect headshot in Sniper Elite, or the trail of motorised destruction in Burnout, it’s important to remember that games are, if nothing else, a fantasy. Actions here are largely devoid of consequence. They’re a virtual playground where indulging in behaviour which is unacceptable in reality, is fine. Human nature pushes us to test boundaries, whether this is our own skill at a particular task or a more grandiose goal, such as space flight, games provide an environment in which we can do these things free of the ramifications that accompany such shenanigans.

The concerned individual may ask about violent games’ effect on children. I’ve written before that this is the responsibility of parents; to control what content their children view and to ensure that their children understand that driving recklessly, hurting the people, and creatures around them, is not acceptable behaviour.

The final point often made about gaming, is that it is an anti-social activity. This particular argument is swiftly crumbling in the face of the rise of the MMO, and other online gaming trends. These days it’s very easy to fire up a console, phone or PC and connect with anything from dozens to thousands of other people at the same time.

Upon the expected retort of “what about single player only games”, it should be noted that being alone from time-to-time is not an inherently bad thing. Retreating from the world and not talking to anyone for a few hours is a fantastic way to relax, and relaxation is vital for slowing the aging process thus gaming can be used in the maintenance of both physical and mental health.

Communicating games to the uninitiated can be a tough task, it can be daunting, and it can test your knowledge of gaming, but it is well worth trying. You may learn something and the ever growing hive mind of gamers will only expand through assimilation!

Dragon Age II PS3 Trophies

Dragon Age II PS3 Trophies Batman Arkham Knight: Freeze Blast / Gun - hidden gadget location

Batman Arkham Knight: Freeze Blast / Gun - hidden gadget location F1 2015 (PC) beginners guide and tips to control

F1 2015 (PC) beginners guide and tips to control Metro: Last Light Redux Achievements List

Metro: Last Light Redux Achievements List Dark Souls 2 Enemies Guide - Part 4

Dark Souls 2 Enemies Guide - Part 4