I’m very interested in systems.

So the other day, after I talked with Raph Koster and read his essay, A Letter to Leigh, I wanted to respond to some of the things he says about systems. There are a lot of interesting points in that article that get tangled together because, of course, there’s no untangling the political from anything. But I can adjust my focus, and I’d like to focus on his starting point, which was that he saw a lot of recent art games messing around with player agency, and if messing around with player agency really had a future as a design technique. He asked whether or not those games weren’t using systems enough or in interesting ways or if that sort of trick could only get a couple of really good uses out of it before players caught on. He’s not wrong to ask any of these questions; they’re really good ones, so here is my answer.

I think the trick that these games use—That Dragon, Cancer, Dys4ia, Brenda Romero’s board game Train—games that appear to give choice but really don’t, just let you sort of helplessly experience what they have, is actually the only trick we have. There are not some games that subvert player agency, and others that grant it. Rather, all games, by nature of being games, by nature of being systems, inherently restrict player agency in the exact same ways. The difference between the games with this “aesthetic of unplayabilty” (as Koster calls it) and any other game is nil. Other games are merely better at hiding their true nature.

I’m going to talk about Raph Koster but this essay isn’t about him at all. I question whether there is a difference at all between this games that subvert and refuse player agency and those that encourage and celebrate it. I wonder whether player agency, as we know it, this quality we assume games just naturally have, is actually an illusion. Koster implies that games are capable of create dialogue with their systems; I believe games can only make statements.

I would like to respond to his first question:

"Does choosing non-interactivity as the central defining characteristic effectively put you in a broadcasting position, and therefore turn the games into monologue rather than dialogue?"

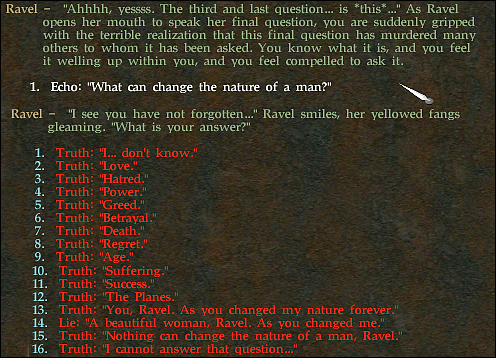

What Koster chooses to define as interactivity here is choice. He believes that interactivity, as well as dialogue, are things that arise from giving players choice. Here's an abstract example of why I don’t believe it: I, the designer, give the player a choice between two premises. It seems I am offering the player the choice to participate in a dialogue, to vote yes or no. But I, the designer, got to choose what those choices were. I control the player's options because I control what their choices are. Dys4ia offers one choice. BioShock offers two. Some games offer millions. All the choices in these games exist as part of limited, self contained systems invented by human beings with definite agendas, beliefs, and politics.

What Koster chooses to define as interactivity here is choice. He believes that interactivity, as well as dialogue, are things that arise from giving players choice. Here's an abstract example of why I don’t believe it: I, the designer, give the player a choice between two premises. It seems I am offering the player the choice to participate in a dialogue, to vote yes or no. But I, the designer, got to choose what those choices were. I control the player's options because I control what their choices are. Dys4ia offers one choice. BioShock offers two. Some games offer millions. All the choices in these games exist as part of limited, self contained systems invented by human beings with definite agendas, beliefs, and politics.

Consciously or unconsciously, we can't help but limit the terms of dialogue as designers because we create them. This is why though a video game may appear to contain a dialogue between two different viewpoints for “the player to decide between” the entire terms of that dialogue are set by the designer, not the player. Designers can and frequently do throw their own prejudices behind these viewpoints. It may seem like a dialogue to offer the player two opposing questions, but it is in fact the opposite: by offering two opposing choices, you have made the claim, through your system, that only opposing binary choices exist in moral situations. Though a game with a good/evil morality system appears to be a dialogue between two points of view, it is actually a statement: that the world is a morally definite one. Your systems can never be infinite, so what makes it into your system can only be what you, the author and designer bring. Your system will be as flawed and human as you are.

A game with one choice is no different than a game with two choices, or a game with ten thousand million choices, because these choices function as part of a larger system, and a system cannot help but make claims. Perhaps a platonic system independent of humans, shivering rhythmically within a computer’s guts can be truly apolitical, but the moment that system touches a human being, that system will begin making claims whose consequences you must be prepared to face. Look bigger than video games: look to any country with a culture and political system and economy and see how an indescribably complicated system still brutally restricts freedom and choice.

So to the other question Koster asks, almost rhetorically, "isn't dialogue the best way to create empathy?" I would have difficulty answering in the affirmative. Not because I don’t think dialogue is a way to create empathy, but because dialogue requires a statement and a response, and systems are statements. Games can be fantastic statements to respond to, like any kind of art. But they do not contain the mechanisms to respond to themselves. Dialogue happens in my response to your system.

I believe Koster believes a dialogue is possible within a system, but I think systems prevent dialogue by their very nature. After all, the designer has written the very rules of dialogue. How can I possibly have a dialogue if I don’t agree with those rules in the first place? In a game with only good or evil choices, how can I make the claim that shades of grey exist, when the game will literally only allow me to respond with black or white answers. I need to go outside of the game’s system in order to do so.

So I do not believe systems to be a dialogue: I believe it to be a human being struggling in a system. No matter what I do as a player, I will never be able to change the hard coded rules in this game. But dialogue of a different sort is possible. Do films and books contain dialogues? The best ones I think certainly do, without a system, without choices, without mechanics. And they certainly also create empathy. But it is always a dialogue between the creator and herself, not between a reader and the creator.

I see games every day that, while they appear to provide choices—a dialogue of sorts—they actually do not. Yet game designers seem to really believe that they are offering true, player determined choice. To pick a recent example, from Daniel Golding's review of BioShock Infinite: ''We are trying to pose these questions and let the player decide how they feel,' said BioShock Infinite’s design director Bill Gardner an interview before the game’s release. On the ‘question’ of violent public humiliation of an interracial couple, BioShock Infinite wants to let the player ‘decide how they feel’.”

BioShock Infinite allows the player the choice of being a violent bigot or taking up arms against racism. Is this a dialogue? Certainly not. Both choices enforce the same thesis: racism is evil. I believe that it should be possible to provide many choices that provide depth and nuance. But even if such a feat is accomplished, it will still be a limited and specific vision: a single voice that speaks in many, perhaps quite contradictory ways, but never a dialogue. A system created by a human will always contain a limited human vision of how the world works. Necessarily, it will make claims and statements, no matter how wide the system is given and no matter how much room for player “agency” is allowed.

Like Koster, I see games as systems. And of course, I also see those systems as creating meaning for players totally independent of their aesthetics. Here is where I lean differently: rather than seeing those systems as avenues for choice and exploration and emergent behavior, I see those systems as inherently restrictive.

To provide a choice is to exclude all other choices. To provide a way to win is to provide infinite other ways to lose. A system that values some choices and behaviors will necessarily devalue others. A system might offer all sorts of pleasant choices to some, but for other participants, there will be no choices that do not oppress or do violence to them. Certainly struggle for meaning and value is possible in such a system, but that doesn't change the fact that a system can be an instrument of hate and violence. A system is not a dialogue. In fact, it can by an instrument that specifically removes the possibility for dialogue (though thankfully, the opposite is also true).

Ah, I've stopped talking about video games.

This is starting to sound almost exactly like a discussion of how cultural and societal systems constrain human beings into binaries of sexuality and gender and race. Well, of course it is. And this is part of the reason why I find systems of all kinds so fascinating, beautiful, terrible, and worth talking about. The systems that govern game worlds are not unlike the systems that rule our everyday lives. I believe that this is a key area in which game designers, engineers, can learn a great deal from the way that social justice, feminism, and queer theory have examined the systems that govern our everyday lives. Study of these systems has a long and rich history. The rules of society are not inherently different from the rules of a game; understand how human social, cultural, and political systems function, and you will understand how they function in games much better. It is very difficult to come away from even a cursory survey of these fields with the belief that systems are not restrictive and oppressive.

I know that at this point emergent gameplay arises to overthrow the claim that designers control everything about their games, the sort of holy grail by which we are able to break out of constraining systems. I think this power is real, just as there are real ways to express and find an identity in a system designed to quash it. But that doesn't mean that systems aren't still restrictive, don't have agendas, aren't political, just because it's possible to struggle against them. Ian Bogost's article on Shit Crayons sort of sums up my feelings on this. Should I celebrate our culture’s horrifically repressive notions of gender and sexuality just because they allowed for emergent queerness? Or should we see the system as a consciously flawed and limited one, with horrifically prejudiced claims that took centuries of struggle to overthrow?

If Raph feels like games like Train, Dys4ia, and Howling Dogs are playing him, I must answer: every single game I have ever played feels like it’s been playing me. I believe a game can have a dialogue with itself; just as any creative work might reflect the complexity of an author's unresolved or contradictory feelings. I believe that as a reader or player, my personal response to struggling within a system or reading a book can certainly be the other side of the dialogue. But it is necessary that I express my response outside of a game, because within that game, I am ruled by your system. You wish for me to have a dialogue with you? How can I, within a system of dialogue whose every term was decided by you?

Certainly rules change; games get sequels, MMOs get patched, governments pass new laws. This does not absolve any of these systems for the claims that they initially made, nor does their potential to change mean that they any individual snapshot of a game does not make inflexible claims. Perhaps games will change in response to social pressure; this makes them exactly the same as all other forms of media.

Train, Dys4ia, Howling Dogs: these games have not "given up" on whether rules can accomplish their goals, because they are clearly accomplishing their goals with rules. And certainly, this is not a one time trick to be used once and moved past, due to the very fact that so many games using it exist. Games are able to use the same trick effectively in new and fresh ways. I am sure, from reading Raph's post on how each genre of game is really only one game, that he would agree that an endless amount of work can be done through the medium of a single system. I am as excited as he is for the discovery and creation of new systems, but if an old and tried system can get the same job done, I don’t care at all.

A lot of the research into systems supports this. When I see analytics used to discuss and predict player behavior, I tend to also see a host of marketing professionals eager to use this data to make players behave in ways that they want. Certainly I'm not a huge fan of this particular application, just as I am no fan of manipulative writing, but I am a huge fan of uses words and systems to convey meaning to other people. I want people to feel things, I guess, so I have spent a lot of time looking for ways that I can do that. Normally I use words, and now that I've spent so much time learning about and making games, I want to use systems to do the same. I would like to create systems that might, for example, make more free and open statements about identity than the ones that we currently live under. Or I might like to make a system that emphasizes those oppressive features in order to indicate what life is like living under a system that feels as restrictive as it is.

I believe systems are statements. Not always restrictive or exploitative of hateful, but always statements. Statements about what choices are allowed. Statements about the limits of freedom. Statements about what categories exist, and what it means to belong to them.

Andrew Vanden Bossche is freelance writer and cutie evangelist. Read his unsystemic emotionsy hipster ramblings at mammon-machine.com and experience an endless stream of his anime brattiness on twitter @mammonmachine.

Top 15 Best Platform Games on PlayStation 4

Top 15 Best Platform Games on PlayStation 4 Dogmeat: Fallout 4 - Find and Recruit dog as a companion

Dogmeat: Fallout 4 - Find and Recruit dog as a companion Review: Corsair STRAFE Mechanical Keyboard

Review: Corsair STRAFE Mechanical Keyboard Wolfenstein: The Old Blood – How to Find all the Nightmare Levels

Wolfenstein: The Old Blood – How to Find all the Nightmare Levels Dissecting The Narrative Of Black Ops 2

Dissecting The Narrative Of Black Ops 2