For a world of kingdoms, peoples, politics and cultures, Gaia lacks depth.

Whereas Final Fantasy VII had the global conglomerate Shin-Ra, and Final Fantasy VIII had PMCs (in the form of Gardens), to its fault Final Fantasy IX references distinct principalities and hinges conflict on the believability of war between them. Kuja, the big bad, seduces Queen Brahne of Alexandria to devastate and conquer its neighbouring kingdoms, Lindblum, Burmecia and Cleyra. These four form the majority of life on the Mist Continent, which in turn claims priority over the other three continents, each named with respect to culture on the Mist.

Contrast between the two quartets raises curiosity. Technology on Gaia is limited to what can be used as fuel — airships on the Mist Continent are powered by the atmosphere of mist hugging the landmass. On the worldmap airships bustle through the skies, representing the population’s reliance on mist and granting an impression of activity.

Since the mist ends at the continent’s shores, travel overseas is inhibited. The Outer Continent, home to Kuja’s super secret baddie base, is accessible to the Mist by boat, although only really from Alexandria (perhaps contributing to its becoming his outlet for strife). To the west is the Forgotten Continent, whose impenetrable cliffs deny entry from the ocean. Perpetual twilight bathes this land in a not-so-subtle metaphor. Lastly in the northwest and farthest away from the Mist lies the snow-covered Lost Continent. Whereas the islands of the Forgotten house a scholar’s paradise, the Lost Continent’s only village is settled for holy pilgrimages.

Since the mist ends at the continent’s shores, travel overseas is inhibited. The Outer Continent, home to Kuja’s super secret baddie base, is accessible to the Mist by boat, although only really from Alexandria (perhaps contributing to its becoming his outlet for strife). To the west is the Forgotten Continent, whose impenetrable cliffs deny entry from the ocean. Perpetual twilight bathes this land in a not-so-subtle metaphor. Lastly in the northwest and farthest away from the Mist lies the snow-covered Lost Continent. Whereas the islands of the Forgotten house a scholar’s paradise, the Lost Continent’s only village is settled for holy pilgrimages.

Here, sensibility ends.

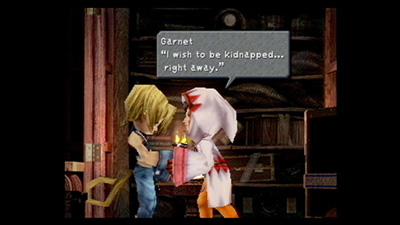

It’s more than a disc until protagonist Zidane and co venture outward from the Mist and just over two discs before Kuja’s pretence as an arms dealer is dropped completely, so it is vital for the player to believe in the legitimacy of a war between Alexandria and its neighbours. For this, at a very basic level, we need to believe in each nation conceptually.

Geographically the division fits: the four cities are separated from one another by a wide expanse of mountains. Simply by walking around the worldmap the player is faced with these natural borders. Secluded Cleyra boasts a perpetual, ‘impassable’ sandstorm as its castle walls, presenting as insular but self-sufficient. The other three claim long-held (and largely withheld) histories of communication and treaties; the presence of border-controls establishes the lands within them as realms.

And yet, despite the impressive expanse of each capital city, the kingdoms are otherwise deserted. For Lindblum, its enormous city walls and quartered districts encompass the entirety of its domain. Burmecia is similarly solitary, although Gizamaluke’s Grotto could be considered part of the parish if you’re feeling generous. Alexandria has only itself and tiny Dali, a formerly agrarian village serving from the game’s outset as a front for black mage production.

Above the mist is inhabitable land void of towns and villages, contrary to each nation’s supposed grandeur. Unknown to themselves, these are kingdoms without peoples operating on non-existent economies – there are no farms or crops, no trade settlements, no exterior impact from the war-torn capitals. When the mist then dissipates, grounding airships and halting trade routes, nobody notices but the bored pilots. If the Mist Continent houses the brunt of this world’s civilization, Gaia is empty.

Nevertheless, with the implementation of two features Final Fantasy IX fools the player into believing its pseudo-political yarn.

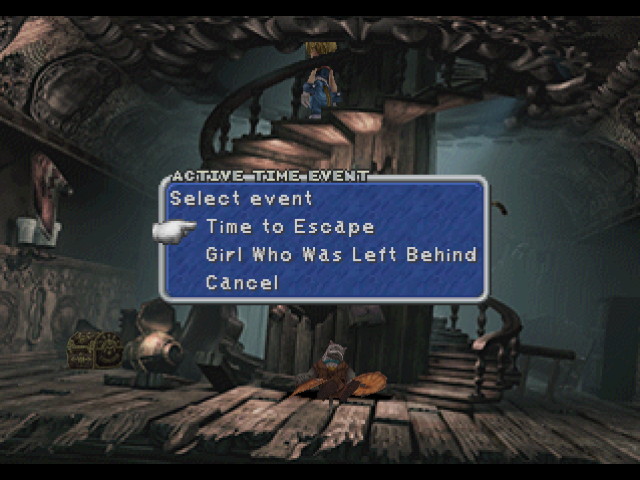

The first is the forgettable yet inspired Active Time Event. At particular intervals the game alerts the player to events occurring elsewhere in the world that can be viewed if desired. What constitutes the ATE is an unobtrusive pop-up at such an occasion, the pressing of select to consent, perhaps a menu to choose an event if multiple are available, and a short cutscene, usually no more than a minute long.

The ingenuity of the ATE feature is how it endears the world to the player. On entering a new location, Zidane’s party disperses to accommodate each member’s taste. ATE then allows the player to experience the adventures, introspections and developments of whichever character sparks his/her fancy. Not interested in Quina’s hunt for local cuisine? Pick the event corresponding to Vivi’s existential crisis. Or perhaps you might feel Freya has seen too little of the spotlight lately. Event names only allude to their narrative so whether the sequence relates to your character of preference is a gamble — albeit a safe one had you been paying attention to the plot.

By allowing the player access to these optional cutscenes, ATE invites him/her to engage with FFIX’s supporting cast. These additional segments characterize the crew on their own terms and not as extensions of Zidane and his exploits. This builds player relationships while simultaneously delivering non-intrusive exposition and world-building. Children in Dali taunt and annoy Vivi, foreshadowing the revelation of black mages as artificial constructs. Eiko empathizes with a stunned Dagger, acting outside of her role as Zidane groupie. Amarant discloses his backstory to Freya, explaining his animosity for Zidane while conveying his newfound respect for the Burmecian Dragon Knight. The player opts in or forgoes as suits his/her leisure.

By allowing the player access to these optional cutscenes, ATE invites him/her to engage with FFIX’s supporting cast. These additional segments characterize the crew on their own terms and not as extensions of Zidane and his exploits. This builds player relationships while simultaneously delivering non-intrusive exposition and world-building. Children in Dali taunt and annoy Vivi, foreshadowing the revelation of black mages as artificial constructs. Eiko empathizes with a stunned Dagger, acting outside of her role as Zidane groupie. Amarant discloses his backstory to Freya, explaining his animosity for Zidane while conveying his newfound respect for the Burmecian Dragon Knight. The player opts in or forgoes as suits his/her leisure.

Some ATEs, however, are mandatory. At such times, a greyed-out ATE pop-up alerts the player to events elsewhere and the scene cuts away. In this manner, the game uses established mechanics to break the flow of protracted cutscenes, interspersing them with comedy, action or drama before returning right where it left off. JRPG cutscenes are of notorious breadth, but here an excuse is given to present them in bite-sized chunks. Meanwhile, what would be a jarring cut-away is legitimized by the use of internal game logic. Accustomed as the player is to opting in to ATEs, a reflexive press of the select button signifies consent regardless of redundancy.

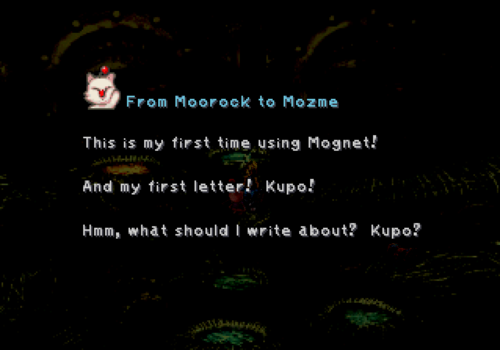

If ATEs describe Gaia one scene at a time, Mognet makes it a connected world. Acting as save and rest points, moogles can be found in every city and dungeon throughout the game. The iconic Final Fantasy creatures here offer a new narrative function in the form of a letter-writing community. As Zidane travels the Mist Continent and abroad, he serves as a postman for each moogle’s correspondence as they discuss personal relations, plot beats or simply local news.

Not only does this turn the fuzzballs into one elongated subquest, it draws a line between each consecutive story location and connects the characters in one area with those in another. These are NPCs with names, with friends and families delighting in their communications and relating to the world around them. Even if it wasn’t tied to such an adorable community, Mognet would still dismantle the trend of a disconnected, autonomous population.

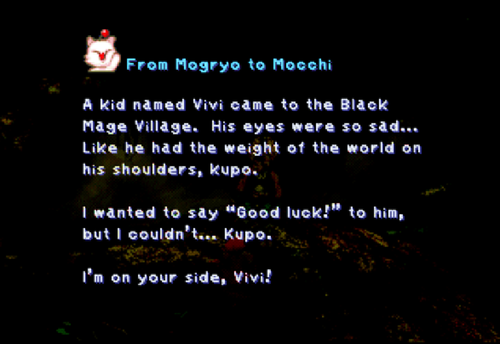

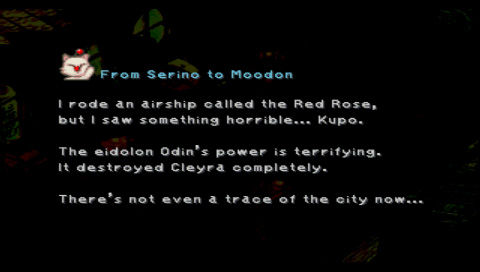

On the other side of things, through the use of Mognet Final Fantasy IX enroots player-specific events to the virtual world at large. As with ATEs, correspondence between moogles depicts a world relative to the participants, momentarily dethroning Zidane (and the player) as the centre of the universe. Mopli’s letter to Serino advertises his fear at Cleyra’s impending invasion; should the player excel at the jump rope, Kupo namedrops Vivi to Monty as Alexandria’s new skipping champion.

Despite the player being central to most news mentioned this way, it is the event itself and not Zidane’s often nominal presence that garners each moogle’s interest. In the face of the medium’s limitations and the game’s streamlined map structure, solipsism is averted.

In thematic terms, moogles epitomise the endearing spirit of Final Fantasy IX which delivers gravitas to its narrative of destruction. Stretching the length of Gaia and beyond, this thinly spread transnational society represents a pacifistic and nurturing culture united against the backdrop of war by the quaintest of things – a postal service. Through their letters the player sees terror at the dread power of Kuja and sorrow for the refugees left behind in his wave. From this perspective, it is easy to rally against the story’s villain if only in seeking to protect the moogle’s cherishable community.

Though Gaia may be incomprehensibly populated and senseless in structure, in establishing a narrative between interconnected denizens it is presented to the player as one contiguous world. Above all else, even if you don’t agree that the world needed saving, how could anyone not love a moogle?

Header credit: Randis/DeviantArt

Mario Bros Inspired 8

Mario Bros Inspired 8 Review: Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor

Review: Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor Madden NFL 12 Game Guide

Madden NFL 12 Game Guide Top 20 Tips for Fallout Shelter Players For Better Results

Top 20 Tips for Fallout Shelter Players For Better Results Destiny: The Taken King Guide On All King's Fall Raid Secret Chest Locations

Destiny: The Taken King Guide On All King's Fall Raid Secret Chest Locations