Details are still sketchy when it comes to the Xbox One's used game situation, and no one knows for sure yet whether Microsoft's next generation of console will allow for pre-owned titles to be played on the system. But where there's smoke there's fire, and it seems more than likely that things are going to change.

While everyone is talking about the future of used games, I think about another practice that is slowly vanishing under the rise of an "always online" architecture and a wide shift in game "ownership" control: renting games. Outside the U.S., and for many within it, renting is the only access they have to a wide variety of games. This was the case for me.

Between 1995 and 2000, my hometown had four different movie/video game rental locations. VideoMax, Servideo, VideoPlus and Videotron. The last and only remaining one is part of a chain of video rental stores owned by Videotron, the ISP and cable provider who are themselves owned by Quebec’s media giant Quebecor. This could be the story of the small mom & pop stores driven out of business by the big corporate giant, and it kind of is, but I’d rather tell the story from the perspective of some kid, growing up in the mid 90’s, who loved to rent video games, and saw the rise and fall of what I’ll call the Cartridge Community.

My most diverse gaming experiences go back to the late 90s. In the early summer of 1994, my father bought my brother and me our first gaming console, an NES. By then the SNES was already out, so he bought it cheap at a flea market with two games: Super Mario Bros. and Tetris. Even though we never made it through world 8, SMB brought us hours of fun. Around the same time, one of our aunts bought an old movies/games rental store. Being bored of playing the same few levels, we asked our parents to bring us there so we could rent a game. And so started a long tradition that would last about 15 years.

We were young and innocent; the internet, with its mass of spoilers, wasn't what it is today. We could still be surprised by a game, discover a hidden gem or be deceived by a cool cover. Through three console generations (NES, SNES and N64), we rented by instinct. Sometimes a game was so bad that we'd bring it back and say it was broken, only so we could get a new one. Over these three generations we owned around 10 games, but we played a hundred of them.

My interest in video games today is in part because of the rich variety I had access to when I was younger. I played the classics on the NES; be it Super Mario Bros. 3, The Legend of Zelda or Megaman 5. I played a variety of obscure games of which today I have only the foggiest of memories. The widest variety came with the SNES. Remember Alfred Chicken, Out to Lunch or Spanky's Quest? All three were platformers with wildly different premises and gameplay. Their quality varied, and they weren’t on par with a first-party Nintendo game, but there they sat on the shelf, no better or worse than the copies of Super Mario World or Super Metroid next to them. Every games had a chance. Today, these medium-sized games are now thriving through digital distribution. They compete amongst themselves, letting the big AAA games fill the aisles of the few games rental locations left.

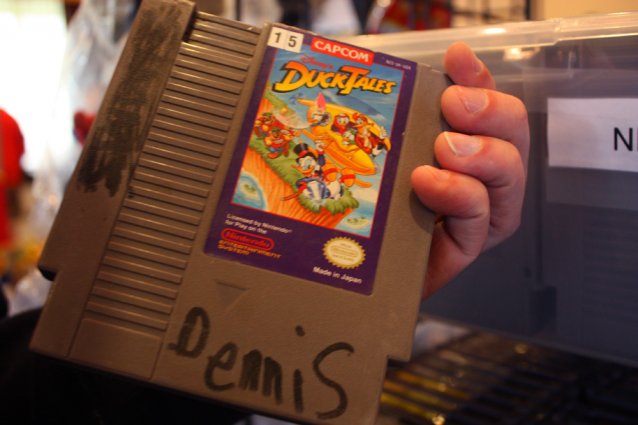

The saved games were kept on the cartridges, meaning that we would all be playing of each other's progress. Through these rented cartridges was formed a community, one where each member was working towards the same goal.

Of course, this would sometimes backfire. I remember having fun exploring and fumbling my way through the fights in Super Mario RPG: Legend of the Seven Stars, too young to understand how save files worked and thus, that I was playing off someone else's progress. Since we were playing of an almost finished file, my brother and I could explore all the worlds. My brother and I were devastated when one day we rented it again and the file was gone. We were now limited to the volcano area, with no knowledge of how to advance the plot. I think we brought the game back to the rental store the same day.

As we got older, making our way through a game became a marathon. To avoid losing a save file, we had two to three days to complete an entire game. Sometimes we were lucky enough to keep our progress between weekends. As games began to support multiple files, there was an unspoken agreement between members of the community not to erase someone else's progress if it could be avoided. The three letters we used to name our files soon became our signatures. We would also ask for particular copies of the game. We didn't want Super Mario World-103, we wanted -102. That's where our file was. If they didn't have it, we'd rent something else.

With the arrival of the Gamecube in 2001, the community died. As games moved to disc, the last remnant of the cartridge generation was no more. We were now costumers, keeping our progress squirreled away on a memory card, where only we would play it. The only trace a rented disc would leave now would be the scratch the last renter left behind. The internet transformed this community too. They became bigger and built around a variety of topics and interests, not single games, single rental stores or a single cartridge.

Maybe it is for the best, but sometimes I miss looking at a box art and renting a game I know nothing about, one that wasn’t marketed to me through specific channels or heavily previewed by the press. Sometimes, I miss the anonymous cooperation of my cartridge community.

Photo: Flickr//Seattle Retro Gaming Expo, Holly Green

FIFA 11 Skills Tutorial - Dribbling

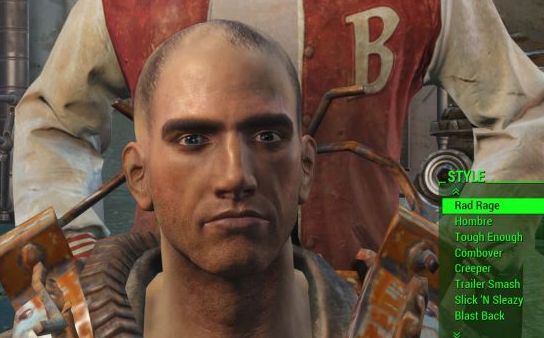

FIFA 11 Skills Tutorial - Dribbling Fallout 4 Guide To Secret Haircuts

Fallout 4 Guide To Secret Haircuts Quickly Improve Your Handwriting with These Fantastic Resources

Quickly Improve Your Handwriting with These Fantastic Resources Fallout 4: Form Ranks walkthrough

Fallout 4: Form Ranks walkthrough Destiny The Taken King Strange Coins Farming guide

Destiny The Taken King Strange Coins Farming guide