After spending most of last week writing about Penny Arcade’s eloquent demonstration of the literally the exact opposite of the correct way to respond to criticism, it was refreshing to see Dennis Wedin of Devolver Digital express to Rock, Paper, Shotgun last Thursday that the developer was thinking seriously about their inclusion of a rape scene in Hotline Miami 2. A lot of comments I see are, grumbling about this decision, accusing Devolver Digital of caving in to outside pressure and accusing critics of encouraging censorship, a comment that goes something along the lines of: “games are a form of art! If games can’t depict topics that are controversial or uncomfortable, like rape, how can we truly call games a way to express or communicate ideas?” That’s a fair point, but it comes from a crucial misunderstanding both of the criticism of Hotline Miami’s rape scene and Devolver Digital’s response to it.

Firstly, it’s important to note that good criticism such as that from writer Cara Ellison, who wrote a preview of Hotline Miami 2’s demo in PC Gamer, contains no such suggestion for restricting or removing content from the game. Her response is instead a description of what Hotline Miami 2’s rape scene does and what it’s communicating—and why that’s something worth feeling uncomfortable about. For Ellison, it’s that the rape scene communicates so little other than violent shock, and the last second framing of it as a film just further trivializes the image. If games are a form of art, and it’s important that we let them use controversial topics to express or communicate ideas, then it’s possible that those ideas might be poorly communicated, or that the ideas may be lazy, not well thought out, or shallow. The art argument only has weight when there’s any sort of aspiration—otherwise, bad story and lazy cliche deserve none of your sympathy. If you are inclined to not forgive games that have unpleasing visuals or awkward gameplay, don’t let clumsy ideas get a free pass.

Devolver’s intention for the scene, as explained by Dennis Wedin in the RPS interview, was quite different. He explained that stopping the rape scene at the last second was a conscious choice to not take the easy way out, to go from gore and violence to sexual assault as a cheap and gross way to up the ante for the sequel. Intent, however, is a word that means “what I wanted to say, not what I actually did” and this in fact is the actual issue at stake in the controversy, which RPS interview Nathan Grayson pointed out immediately: lots of people shared Cara Ellison’s reaction, while very few, not even the loudest defenders of the rape scene, got the meaning out of the scene that Dennis Wedin mentioned in the interview—and that’s the real reason Devolver has taken out the scene for the time being. “It didn’t come out the way we wanted it to. So that’s why we took it out,” said Dennis Wedin, which is, frankly, kind of amazing in the way that the video game industry meeting a minimum standard is often amazing.

I don’t actually mean to trivialize this response to criticism though, because it can be very, very easy to blame an audience for “not getting it” when it’s just as likely, and often much more so that the problem is on the end of the artist rather than the observer. Certainly, they could complain that people just don’t get it, as many have but Dennis Wedin seems to not share that attitude: “I don’t think it’s right to just say, “You’re wrong. You’re just looking at it wrong.” That’s not the way to go.” He’s correct: though games really do communicate ideas (and of course they do) intention does not always pan out. If no one is getting what Devolver wants out of this particular scene and getting a rather whole lot of unintended awfulness on the side, it only makes sense to withdraw the scene until they can make it do what they want it to do. This sort of feedback response is utterly commonplace when it comes to mechanics and game design—how else could developers craft their work? But it seems that for some narrative criticism occupies a different space, when it’s really no different at all.

This is why Cara Ellison’s initial criticism of Hotline Miami 2 was so crucial, and so necessary, despite the rage with which her criticism was met in the comments on her preview. Curiously, the actual developer of the game in question had no overwhelming negative reaction and did not choose to harass her on twitter or on comment threads, but instead took the criticism seriously—which signals that they take their own work seriously. It remains to be seen how Devolver Digital handles the final product, as the result isn’t guaranteed to be better than their initial attempt. However, they still see the criticism as something that must be addressed in order for their work to grow from intention to reality. Listening to criticism means taking it seriously, not obeying it without question or dismissing it outright. I hope in the future to have more weeks where the biggest drama in video games is that someone listened to a nuanced critique.

AVB is freelance writer and cutie evangelist. Read his unsystemic emotionsy hipster ramblings at mammon-machine.com and experience an endless stream of his anime brattiness on twitter @mammonmachine.

inFamous First Light PS4 Complete Part by Part Walkthrough

inFamous First Light PS4 Complete Part by Part Walkthrough Advantages / Disadvantages of Digital media on Xbox One / PS4

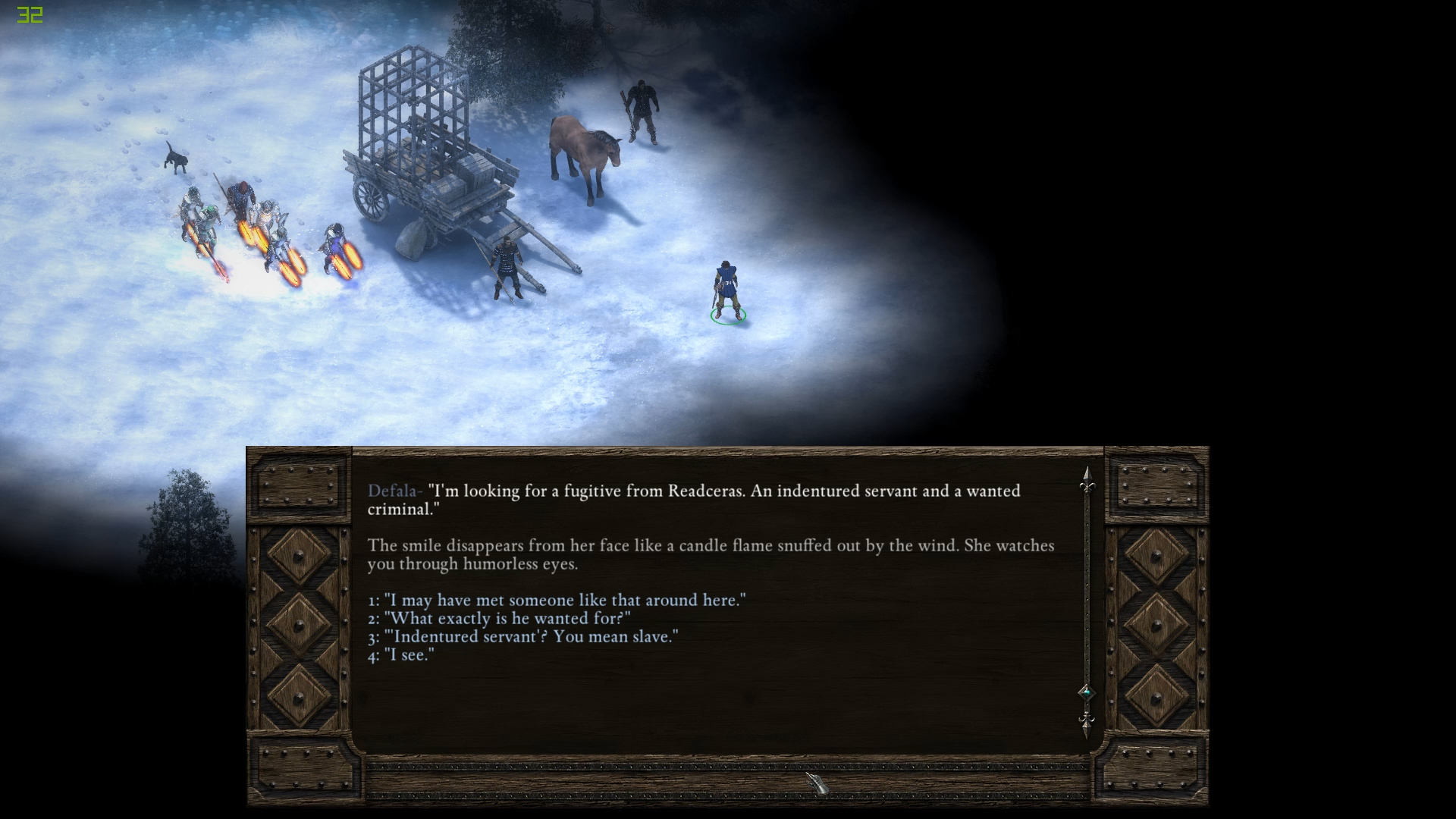

Advantages / Disadvantages of Digital media on Xbox One / PS4 Pillars of Eternity the White March Side Quests, Tasks, and Companion Guide

Pillars of Eternity the White March Side Quests, Tasks, and Companion Guide Destiny The Taken King: How to Prepare for King's Fall Raid

Destiny The Taken King: How to Prepare for King's Fall Raid Review: Endless Legend

Review: Endless Legend