Kotaku has an audience of eight million people, according to editor-in-chief Stephen Totilo, making it the social equivalent of a thermonuclear device, equal to a little over 80% of a Kanye in power. That is a lot of eyeballs and a lot of potential comments to send in the way of anything they are linking to, and while that is mostly fun and innocent when the link is to a lovely cake themed around Minecraft or a Minecraft map themed around a cake, on more controversial issues that is a lot of potential jerks to send someone’s way. Even if assholes are only, say, 1% of the population, which is the most ludicrously conservative estimate possible, that is still Eighty Thousand Assholes. That is a lot of assholes, far more than any one human being might be reasonably expected to deal with.

Whatever the real number, it’s beyond question that the sheer degree of harassment suffered by a journalist yesterday at the Xbox One Event at Eurogamer Expo was exacerbated to absurd, unconscionable levels yesterday after Kotaku covered the story of her harassment. When people who speak out against harassment are terrified of media coverage, as she was, journalists have a problem. The person in question wanted nothing more than for the article to be taken down, regretted it was ever published, and is almost certainly far worse off for the article being published than had it not been published.

This isn’t just a problem for Kotaku, but for any journalist who wants to cover stories of harassment: how is it possible to cover news that is happening in a way that does not compound the harassment by drawing attention to them? How is it possible to make sure the attention is focused on the harassment, not on the victim of harassment? This is complicated, because covering these stories can be important—Stephen Totilo believes covering stories of harassment is important, and I agree. I believe Kotaku does sincerely believe in bettering the gaming community, opening it up to diverse voices, and ending harassment and abuse, and that publishing stories like this is part of the process: forcing our community to acknowledge when terrible things happen.

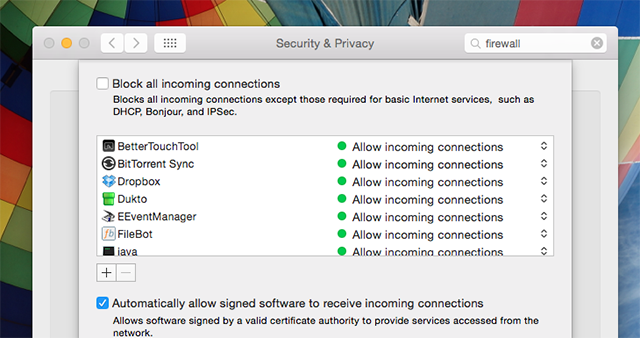

This is important work, and it is such important work that the utmost care and responsibility should be exercised in covering these situations. Kotaku has already taken steps to address one of the most prominent problems with covering the story which was that by directly embedding a person’s tweets, they gave readers direct access to communication with that person. It’s not unlike including someone’s phone number along with a recorded statement by them. Stephen Totilo’s position has been that since Twitter is a public area, publishing them is fair game—it’s like overhearing a sidewalk conversation. For public figures, this practice, while gossipy, seems not directly unethical—prominent industry people like Cliffy B, Jon Blow, or Hideo Kojima already use Twitter as a way of addressing the public, but not everyone does. Many users simply use Twitter talk to their friends or small groups with common interests. They are speaking as if they are in, say, a bar or cafe—not making public addresses or announcements. Public figures already have their every tweet scrutinized by the press and public, but private figures don’t have this attention unless it is foisted upon them, and while there is no direct legal precedent for this situation, it is clear that the effect of drawing eight million readers to a private figure will impact their lives much more severely than to someone who already has 200,000 followers. In legal cases involving breech of privacy, the harm is calculated by damage in the form of mental anguish, it certainly could qualify the victim of harassment in the Kotaku article this weekend.

However, there are further issues with embedding tweets that complicates this practice even further. Like most news reportage, this particular article attempts to have a neutral perspective—but by placing her tweets front and center, Kotaku hyperfocuses on the person in question. Often, this is a desired framing—what better way to tell a story about a person than with their picture and own words right next to it? But by this framing the most visible part of the story is the individual, not the story of her harassment. The news event is not about her as an individual but about her treatment by a Microsoft hired entertainer at a Microsoft sponsored event. That’s the story, but with her name and face visually repeated throughout the article, the story becomes about her more than it does about the comedian who harassed her (whose name appears once) the harassment itself, or the Microsoft sponsored event it happened at. Telling a story almost solely through her tweets conveys to a readership that the most important part of the story is who is speaking and what she said—not the events she described happening to her. This is not the same as designer announcing something or making a professional statement. Though this framing has the appearance of neutrality, since it lets her words speak without commentary, it actually shifts focus from the actual event to a person, and not even the person being accused of harassment and dehumanizing behavior.

Furthermore, Kotaku’s audience is not an entirely neutral party. There are, I am sure, beautiful and lovely readers of Kotaku (though not as beautiful and lovely as readers of Gameranx (especially those who got far enough in this article to read this)) but there are many more who are not, and because dragging terrible people around is an inevitability, the way that these news stories are framed can never ever be truly neutral. If there is a virulent streak of transphobia in a readership, minority or not, then a story presented as completely neutral will not be read as such by them. They will see it as an invitation to “disagree” with the subject of the article, which they will use as license for harassment. What reads as neutrality to one group will read as endorsement for attack to others, and when that is a known and understood risk, writing a truly “neutral” article cannot ever be possible. Journalists bear at least partial responsibility for how their audience’s reactions because they are the ones that frame these stories. If Kotaku truly feels that covering harassment is important because harassment should not be tolerated, even standard news stories should reflect that attitude, because what a reasonable person will read into a “neutral” story is very different from what a bigot will.

Kotaku is a site that focuses on culture and personalities because that’s Gawker’s modus operandi and there’s nothing inherently wrong with that approach. I respect Stephen Totilo’s desire to cover these important issues in our culture and I do believe he wants to make the community better by doing so. However, I also want to make it beyond clear that with these good intentions comes responsibility for executing those intentions in reality. In cases where it is known that harassment can result, I can’t write pretending to be ignorant of the ways in which a readership might react to what I say. I don’t presume at all to tell Kotaku or its staff what its message should be or how to frame it, but I hope Kotaku—and everyone else in the communities surrounding games—will think carefully about how we frame our stories.

Lego Marvel Superheroes Deadpool Bricks Guide

Lego Marvel Superheroes Deadpool Bricks Guide Victor Vran: farming and leveling guide

Victor Vran: farming and leveling guide Minimum / Recommended requirements for playing PES 2016 on a PC

Minimum / Recommended requirements for playing PES 2016 on a PC Fallout 4 Guide: How To Use Basic PC Console Commands

Fallout 4 Guide: How To Use Basic PC Console Commands Fallout 4: Banished from The Institute walkthrough

Fallout 4: Banished from The Institute walkthrough