It took me years to play Assassin’s Creed. It’s not that I had no interest in the series—I’d heard about the rich historical environments, likeable characters, and entertaining stealth mechanics often enough to not dismiss it entirely—but I’d been busy playing other games. And the premise struck me as cool but a bit repetitive.

I mean, climbing buildings to perform assassinations prior to diving headfirst into a haystack or fleeing into a crowd is fun and all, but is it that fun? Is it the kind of fun that lasts?

So I spent a lot of time neglecting the series and offering empty praise whenever it was called upon me to do so by a group of Assassin’s Creed enthusiasts.

If not for the release of Assassin’s Creed 4: Black Flag coinciding with the launch of the next gen consoles, I might still be nodding along to statements like “It features an accurate reproduction of 16th century Constantinople!” and “Remember that time Ezio watched half of his family get hanged?” and “But that Juno lady is pretty crazy.”

But the moment the PlayStation 4 was announced I knew I was going to buy it (calm yourselves: this is context, not empty praise); it was the first console release where I was just financially stable and reckless enough to kiss a third of a monthly paycheck goodbye, and I was going to go for it.

However, I needed a game to start out with.

Initially, that game was going to be Watch_Dogs, but my past self must have sensed that things would go awry—temporarily forestalling my inevitable journey with Aiden Pearce—and opted to start playing Assassin’s Creed in anticipation for Black Flag.

I like pirates and knew that I wanted to hop into Edward Kenway’s pirate boots but am a bit of a snob when it comes to a well-told story. I couldn’t play Black Flag without some working knowledge of the series.

In August, I formulated a goal: beat all of the Assassin’s Creed titles (excluding ACI, which I had seen played previously, and Liberation due to immediate availability and time constraints) before my PlayStation 4 and copy of Black Flag arrived.

This goal was expedited by the announcement of Watch_Dogs’ delay.

I’ve since played all of the games I intended to but, if you’re curious, I didn’t quite make my self-imposed deadline. I actually spent two days staring longingly at my PlayStation 4 and plastic-wrapped game while I finished up Connor’s story.

So, as a recap, I played through Assassin’s Creed II, Brotherhood, Revelations, Assassin’s Creed III, and Black Flag in less than three months and with limited breaks. While the middle three didn’t receive as much attention as I would have liked, I completed the majority of side quests in both Assassin’s Creed II and Black Flag.

Similarly, I also found that these were the two titles that best held my interest.

From the moment Assassin’s Creed II started, I was absolutely captivated by Desmond and Lucy’s fast-paced escape, by Rebecca and Shaun’s mismatched personalities, by the cleverly beautiful way the Animus stitched together Renaissance Florence in grey scale and brushstrokes, by the banter between Ezio and almost every character introduced early on, even by something as unimportant as having to beat up Claudia’s philandering beau.

Assassin’s Creed II was a shining example of what a game can be: serious and humorous, giving the player an in, so to speak, without losing sight of the overall aim of the plot.

I loved the concept of playing as a character playing as another character, loved the way Ubisoft Montreal was creating such a layered game, and especially loved the attention to detail paid to keeping these two elements in focus for the player.

And somehow, despite my conscious knowledge of my remove from Ezio’s plight, I was still touched by the tragedies he went through. I’m not certain I liked Ezio until midway through Brotherhood (he was brash, foolish in his forgiveness, and a bit of a lecher, after all), but I did care about him in the way you care about a person who isn’t absolutely horrible and has fallen on hard times.

I watched Ezio become more and more likeable in Brotherhood and Revelations, which I experienced rapidly—putting in one disc after another, watching him age years and years over a span of mere weeks.

In the grand scheme of things, it was frightening how much I cared about Ezio by the time I completed Revelations (and don’t even get me started on “Embers”). It was like watching a friend grow over a lifetime.

I experienced Ezio’s transformation from naïve young man controlled simultaneously by vitriol and compassion to middle-aged man suffering from a life of duty that allowed for little else.

Remembering the opening scenes of Assassin’s Creed II—Ezio’s carefree nature, his race with a brother he’d soon lose, his love of family and women—that, for me, hadn’t happened all that long ago made it harder to endure Brotherhood and Revelations. In many ways, I was led to empathize with Ezio in ways that a game had rarely provoked in me before.

However, as you might be able to already tell, the way that I played these games affected my experience. Assassin’s Creed II, Brotherhood, and Revelations merged into a single game for me.

This certainly improved the overall character arcs of Ezio and Desmond and even allowed me to more easily to see the ways in which combat mechanics had improved, moving beyond the simplicity of prompt countering in Assassin’s Creed II to offer chained attacks and grappling in Brotherhood and Revelations. But it also highlighted some less than desirable elements that wore away at my initial affection for the series.

For starters, playing these games in rapid secession was tedious. I was tired of the busy work involved—so much so that I gave up on completing the majority of optional side quests half way through Brotherhood—because I felt that the battle between the Assassins and the Templars as well as everything happening with the First Civilization was going to pay off in some rewarding ways, pending any of the games decided not to end with a cliffhanger.

Not only did the monotonous side quests become a problem (Seriously, no more feathers, no more bomb crafting and tower defense. Please.), but the actual objectives of the game became too repetitive and, honestly, a little dull.

As much as I love stealth in games, I’d tracked down targets using Eagle Vision and assassinated them from various hiding spots often enough to lose a lot of interest in the approach. This wouldn’t have been as big of an issue if the mission objectives didn’t limit the player to specific play styles (and punish them for not playing accordingly), but they do so it is.

Again, I had a deadline, which severely impaired my ability to play at a lazy pace and likely facilitated some of my aggravation, but I also really wanted to see what Ubisoft had planned for the world they’d created.

I wanted them to make sense of Juno and her ghostly cohort, Desmond’s heritage and its importance, and the nefarious nature of the sun. I wanted to see something happen between the Assassins and Templars in present day that was unexpected. I wanted a lot of things.

Some of my wishes were granted in Revelations, but the way it played out was fairly unfulfilling, especially considering the hours I’d put in.

So I started Assassin’s Creed III: a game I had not heard good things about, and I came out of my (rushed) play through with similar complaints and even a few new ones.

One thing I’d like to say before anything else, though, is that I didn’t take issue with Ratonhnhaké:ton to the degree that much of the gaming community did. I thought he was a powerful character whose story encapsulated what the struggle between the Assassins and the Templars aims to illustrate.

That is to say, Assassin’s Creed III really shows the multiplicity of choice and consequence; the ideologies of Ratonhnhaké:ton and his father, Haytham, left me considering how similar their respective organizations are and how easily good intentions are felled.

Connor—the name given to Ratonhnhaké:ton when he first pursues the role of Assassin, a moment that excellently depicts how the game covers a good deal of his life—wasn’t a problem. But the execution of his character was problematic.

Thrusting the player first into the role of Haytham Kenway, the game lasts a period of approximately thirty years. That’s thirty years, two “protagonists,” and a number of very tragic stories portrayed in one game.

This doesn’t quite rival the span of time we experience with Ezio, but he was given three whole games. To put it simply, coming off of Ezio’s arc, Connor’s felt hurried. Too many important things happened off screen, keeping the player in the dark, making some developments feel contrived, and limiting our ability to bond with the characters.

I’m not saying that Assassin’s Creed III should have been split into multiple games, by any means, but I am pointing out an important disparity among the Assassins we’re given access to (after all, Altair’s story might appear confined, but he’s given his fair share of time in Revelations).

Perhaps most unfair, in the evolution of the franchise, Assassin’s Creed III inhabits an uncomfortable transitional space. It serves as an end to Desmond’s story as well the immediate, present day focus on the ongoing fight between the Assassins and the Templars; seeks to introduce elements (such as captaining a ship, hunting and skinning, and new weaponry) that appear in Black Flag; breaks away from an established trend of dedicating several games to a single Assassin; and focuses on humor—namely in Shaun’s Animus entries—in ways that contribute to the tone and likeability of Black Flag but simply don’t work in a setting as somber as the American Revolutionary War.

In many ways, for me, Assassin’s Creed III was directly responsible for the success of Black Flag. It continued to remind me of the quests and plot devices I was tired of, and it perfectly illustrated that I was tired of them not just because they had become rote but because the pre-established tone of the earlier games in the series deserved something more thoughtful.

But Black Flag changed that by giving us a character more foolhardy than even the youngest incarnation of Ezio. Edward Kenway is a pirate through and through, and Ubisoft doesn’t let you forget it.

He’s rarely honest, even more rarely sober, and isn’t even an Assassin. Kenway lives by his own creed and, coming into direct contact with both the Assassins and Templars on numerous occasions, doesn’t favor either for admirable reasons until late in the game.

He’s not a good person, but he’s funny and charming in the way that pirates are. And, like any good Assassin (or Templar), I wouldn’t turn my back on him. He also befriends an interesting cast of characters that keep the player interested but don’t necessarily bring the plot to the forefront.

Don’t get me wrong: Black Flag shows a man transform, which makes for a good story any day, but it certainly doesn’t steal the show and it certainly doesn’t require a player to take it too seriously.

Black Flag allows its player—both as Kenway and as a random Abstergo Entertainment employee—room to have fun and not overthink things. Yes, events are still playing out in the present day that relate to Desmond and other subjects that have been developing since the beginning of the series, but they’re minimal and, while contrived in true Assassin’s Creed fashion, don’t require a ton of thought unless you’re so inclined.

Like ACII, this most recent title makes it hard to forget that you’re playing a game as someone else playing a game. Every time you step away from the Animus, you’re surrounded by “other gamers” and the database entries, while comical in the vein of Shaun, focus on manipulating history for entertainment purposes as opposed to functioning as mini history lessons. And, honestly, the approach seems a lot more fitting given the framework.

After all, why would game designers working for modern day Templars take history seriously?

The newest Assassin’s Creed also devotes a lot of time to offering side quests, but the breathtaking setting and sheer variety of missions propels the game forward. I felt much more compelled to pick and choose what I wanted to do as opposed to doing it all out of obligation.

Not only that, but so many of the optional missions departed from those found in the previous games or else rewarded the player (with upgrade plans, for example) in new and interesting ways that made the added effort worth it.

Assassin’s Creed is a series that has seen a lot of changes while still maintaining much of what pushed it to popularity in the first place. After a period of stagnation, it appears the team that designed Black Flag has brought to life something quirky, offbeat, and appealing in a way that keeps the player guessing about the nature of the Assassins, the Templars, and the First Civilization or whether any of them are even that important.

There are still a good many things I’d like to see improve; namely, combat has a ways to go before it achieves the kind of momentum and complexity that I think Ubisoft is working toward.

But one thing I’m happy to say Ubisoft hasn’t lost sight of is how to make characters interesting and sympathetic. They dropped the ball in some ways with Connor, but it’s hard for me to think of any two characters I was more inclined to dislike yet somehow ended up loving than Ezio Auditore da Firenze and Edward Kenway.

And while I’m still waiting for a lot of answers (I mean, seriously, Juno’s pretty crazy. What’s going on?), I’m somehow more content with the notion of waiting now.

Resident Evil: Revelations 2 Wiki – Everything you need to know about the game .

Resident Evil: Revelations 2 Wiki – Everything you need to know about the game . Pirates of the Caribbean 5: Kaya Scodelario joins the cast

Pirates of the Caribbean 5: Kaya Scodelario joins the cast FFXIV: How to Obtain the Pegasus Mount

FFXIV: How to Obtain the Pegasus Mount MGSV: The Phantom Pain - How to Build the Forward Operating Bases Guide

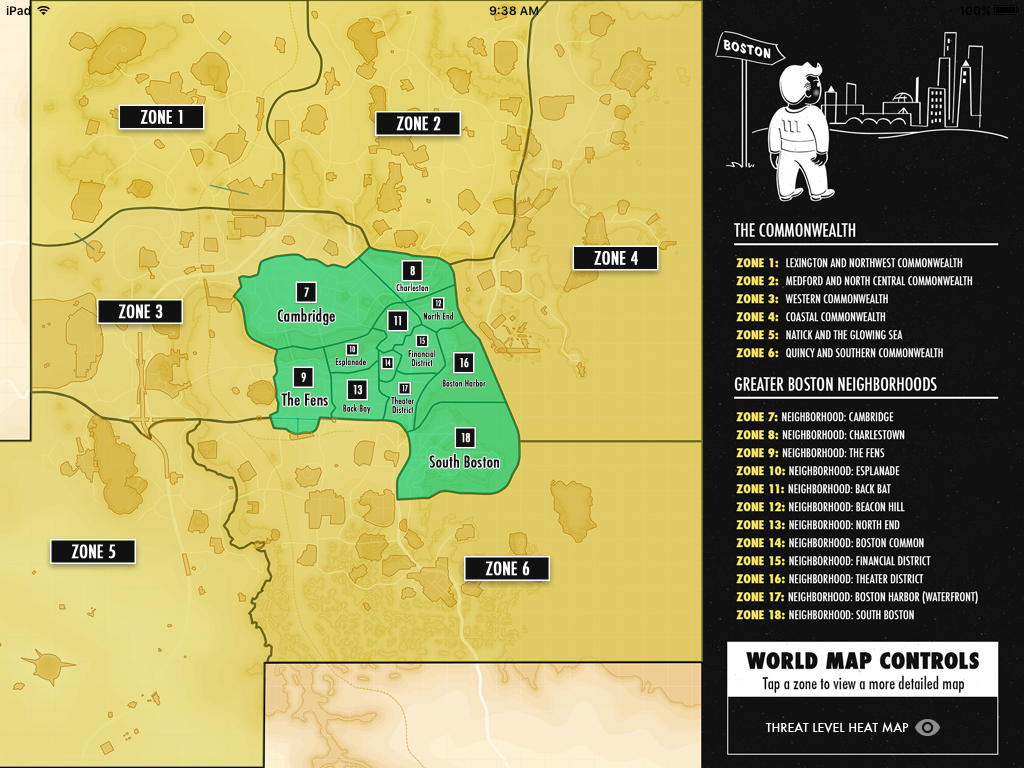

MGSV: The Phantom Pain - How to Build the Forward Operating Bases Guide Fallout 4 Ending: The Nuclear Option Brotherhood of Steel and A New Dawn

Fallout 4 Ending: The Nuclear Option Brotherhood of Steel and A New Dawn