“I am Andrew Ryan, and I’m here to ask you a question. Is a man not entitled to the sweat of his brow? ‘No!’ says the man in Washington, ‘It belongs to the poor.’ ‘No!’ says the man in the Vatican, ‘It belongs to God.’ ‘No!’ says the man in Moscow, ‘It belongs to everyone.’ I rejected those answers; instead, I chose something different. I chose the impossible. I chose… Rapture, a city where the artist would not fear the censor, where the scientist would not be bound by petty morality, Where the great would not be constrained by the small! And with the sweat of your brow, Rapture can become your city as well.”

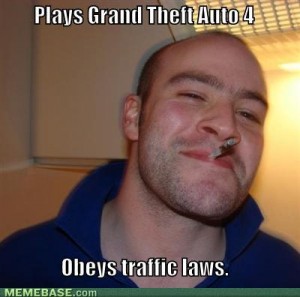

Games are the stuff of unimagined realities, we want reality but we also want the freedom to do everything in a game as in the real world but without having to be morally culpable for our actions. We want things to be different from the real world but have signs connecting the two. Games already are different, being caught by the police for murder doesn’t have the same gravity in GTA as it does in the real world, there’s no trial, no prison and subsequently no rape. In games we want to see and do things we never thought possible, we want to experience things that are impossible and we don’t want to feel restrained by petty morality.

It’s become a recent trend in games to inject some half baked ideas of morality or a moral consciousness into their games, mainly as a way to increase longevity; basically it’s just a cheeky way to get you to play the game twice to see the sickly sweet ‘good’ ending. The reality is there are no such things as moral choices in games because the game can be played again or reloaded to perform a ‘do over’. Sadly morality in games is often as messy in virtual worlds as it is the real, often I praised Mass Effect for having the bad speech options highlighted red and the good blue so I knew how to be evil, or good if I was feeling frivolous.

One of many things Bioshock can be praised for is its stunning Manichaeism and ambivalence, there’s no moral grey area in cracking open little girls like coconuts and sucking out their plothole-filler juices. Although in a recording in the game it’s not described as killing them as it is taking a terminally ill patient off life support, but the alternative is saving the little girls and although you still receive some magical plot-filler-suspension-of-belief-juice you receive significantly less. So the moral struggle is very simple, it’s survival of the fittest, you save them at the risk of your own weakness or kill them ensuring your own survival. Although it’s essentially a clear moral choice where both choices can be rationalized, clear moral choices are in no way realistic, they don’t exist.

Most of the time when you make moral choices in games, just like life it’s hard to establish which is which because morality isn’t something that’s set in stone its fluid. What was moral one hundred years ago is not necessarily the case now, there was a time people thought human sacrifice was up there with giving blood. Not to mention that morality is entirely subjective, one man’s freedom fighter is another man’s terrorist and all that. Often it’s hard to make out if games are teaching us right from wrong or if we’re teaching them, because the idea of ‘right and wrong’ is about as black and white as a clown’s underpants, games almost become a philosophical dialogue. The game takes the role of Socrates helping you develop your own ideas of morality. All in all it doesn’t matter because the people who your choices affect aren’t real anyway, so how can human morality translate into a virtual setting?

7 Tips on How To Prepare And Defeat Any Witcher Contract

7 Tips on How To Prepare And Defeat Any Witcher Contract Infinite Crisis Wiki – Everything you need to know about the game .

Infinite Crisis Wiki – Everything you need to know about the game . A Brief Guide To Critiquing Your Own Photos

A Brief Guide To Critiquing Your Own Photos Top 10 Best PS3 Role Playing Games of All Time

Top 10 Best PS3 Role Playing Games of All Time Bravely Default Review: The Little JRPG That Could

Bravely Default Review: The Little JRPG That Could