The beauty of the best science fiction is that it's only a few decades ahead of science fact: a tantalising taste of the future.

We've seen technology that'd benefit the human race, pioneered in sci-fi novels, movies and games, gradually becoming common additions to our everyday lives. Mundane, even. Daily space travel or teleportation mightn't be in our lexicon beyond fiction just yet, but we do have pocket-sized devices that allow us to connect, interact and experience the rest of the world at the touch of a screen, while hand-sized storage boxes contain an entire life's work of photographs, music, writings.

The human-created exoskeleton, a metal, mechanical frame that encases the human body to aid mobility is more than concept, more than science fiction. While the idea is still being refined and worked on, it does exist in different forms in today's world.

These early designs may be cumbersome, but the worlds of military, science and medicine are iterating on them to ultimately aid with warfare, safety, disability. But with all great sci-fi, the ideas on page and screen are several decades ahead of the actuality: we're still behind the curve.

There's two distinct design strands with fiction's take on exoskeletons: the supersoldier and the mecha. Both have been absorbed into the genre by many creatives, many mediums. But the latter is perhaps engrained best on the social consciousness through decades of Japanese animation and manga.

THE MECHA

The number of series that are built around this common concept are many, be it pilots controlling massive robots in Gundam, transformable fighter jets that convert to humanoid robots in Robotech / Macross or mechanical animals combining to form one giant robot in Ultron, all pull from the same pool of ideas.

Yet the best have put their own spin on the mecha concept. 1988's Mobile Police Patlabor treated their robots - or Labors - as commonplace, used as a labour force in construction, or little more than an everyday alternative to the police car for cops. 1995's Neon Genesis Evangelion altered the perception of mecha being lumbering, slow-moving machines with a trio of lithe Evas, sculpted like Olympians, that could leap buildings in a single bound.

The Japanese love for these creations has also intoxicated the West. Last year's Pacific Rim was director Guillermo del Toro's homage to a childhood watching these cartoons, yet even he added something new to the genre, as his colossal, Kaiju-fighting Jagers were operated by two pilots in mental sync with each other, their robotic form mirroring their movements.

Controlling these mechanical beings varies wildly. Many series elude to a series of joysticks, levers and switches to operate their ride. The idea that the mecha and its pilot are distinct from each other. Respawn's Titanfall offers a nod to this with similar, but different control schemes and abilities between a Pilot and their Titan. Powerful, yet you had to be constantly respectful of slower turning circles and differences from human mobility when suited up.

We saw similar ideas with the VS in Capcom's Lost Planet series, and the Metal Gears in Konami's Metal Gear Solid franchises (which when played in chronological order, allowed you to see the evolution of technology in each subsequent Metal Gear design). Steel Battalion famously was sold with a hundred pound (in price, but not likely far off in weight either) controller that simulated the vehicle's control.

There have been other approaches to try and better mirror the pilot of these exoskeletons, and both have perhaps been best shown in the works of Japanese artist and storyteller Masamune Shirow.

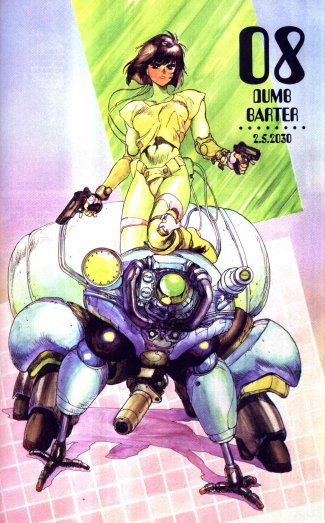

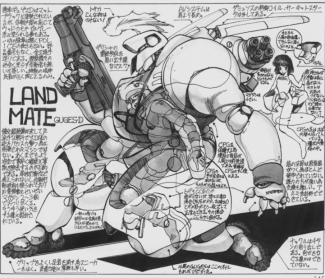

In his critically-acclaimed Ghost in the Shell series, counter-cyberterrorism unit Section 9 had spider-like tanks called Fuchikomas. Pilots would have their cybernetic brains hard-wired into the tank's AI operating system, with the mind link allowing them instantaneous response and control. In his Appleseed franchise, Shirow introduced the idea of a Landmate, a bridge between the two exoskeleton design strands. The pilot would be encased inside the suit's shell, and the Landmate would directly mirror the pilot's movements.

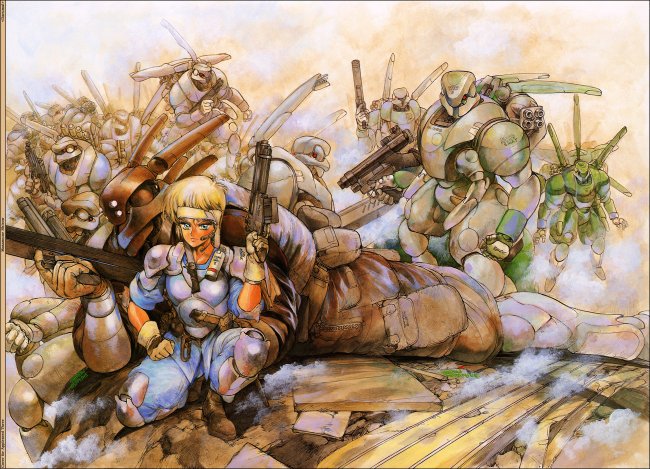

Outlandish though the idea was when he first introduced the series in the 80s, it was grounded in some semblance of reality. His series of art books, the Intron Depot collection, contained detailed schematics on mecha designs that'd service these new worlds, such as the ESWAT Landmates worn by Appleseed's Deunan Knute and her colleagues. You could look at the sketches and believe they could be used to build the real thing.

THE SUPER-SOLDIER

The Landmate was just a bulkier version of the super-soldier concept; an exoskeleton that's more of a conforming fit to the user's body, and increases their strength, agility and ability to superhuman levels.

Operating as both protective armour and weapon, the practicality and realistic builds of these exoskeletons vary from case to case. Neill Blomkamp's Elysium had exoskeletons that formed a skeleton frame over the user, a far more graceful design than what Tom Cruise wears in the upcoming Edge of Tomorrow; a bulky suit that takes effort to move. Yet both are more graceful than their spiritual precedessor, the Power Loader used in the climatic act of James Cameron's Aliens film. That iconic design has been referenced in multiple media, including video-games: you can see it with Gears of War 3's Silverbacks, and the Cerberus Atlas in Mass Effect 3).

Bulky, slow moving. Far-flung futures they may appear in, but the Silverback and Atlas are closer to what we'd imagine would be possible in today's world. That lack of speed and excess weight is something a few works of fiction actively embrace, such as Warhammer 40K's Space Marines, or even EA's Dead Space, the original at least making the clunky engineering space suit a gameplay mechanic as you had to pander to the slower turning circles of the Rig.

Far more realistic than the likes of Marvel's Iron Man (the original design of which, to be fair, was about as graceful as an industrial oven) or the Augmented Reaction Suit in Platinum Games' Vanquish. These exoskeletons give their users access to abilities beyond natural human ability - flight and the ability to slow down time. Other 'suits' in similar categories offer protection and offensive capabilities, such as the Nanosuit in Crytek's Crysis, the upgradable armoured suit worn by Samus Aran in Nintendo's Metroid series, or Spartan's armour in the Halo series.

Then we dig into cybernetics, the fusion of man and machine. Such as in Deus Ex: Human Revolution, the augmentation of muscles and body allowing Adam Jensen to punch through walls and leap great heights thanks to these enhancements. Yet interestingly Masamune Shirow, for all his work on the concept of man/machine interface, tried to enforce certain realities. A cybernetic arm, for instance, would only be able to mirror the original form's abilities and power; trying to use additional strength to lift something heavier than the body could cope with would see the arm pop out of its socket.

We're already seeing cybernetic prosthetics being introduced into the real world. While robotic suits and superhuman exoskeletons are still only a work of science fiction, reality is catching up. Such creations may be beyond our lifespans, but at least we can enjoy what it may feel like using them in the here and now; on console, or on the big screen.