A few quick Google searches was all that it took to tell me this was something of a decisive issue among gamers.

Even among professionals (especially among professionals, I should hope, descent among peers is healthy for any form of opinion-based journalism) the very concept of the console MMORPG is something that’s hotly contested: some are excited about the idea behind them, and are looking forward to playing each iteration in the hope that it’ll finally be the one they’ve been waiting for. Others are skeptics, doubters, who think that a good console MMORPG is just impossible, and attempts to bring the largely PC-dominated genre to the living room is a waste of time—similar to the RTS. And then there’s the middle ground—where I neatly lie—who believe a console MMORPG isn’t IMPOSSIBLE… but it might require a lot more effort than you’d expect.

But with Elder Scrolls Online in full swing on the PC and the upcoming Xbox One/PS4 launch looming, I figured it would be a good time to look at Console MMORPG’s as a whole—why they’re not working, why the Elder Scrolls Online probably won’t work, and what I’d expect a good console MMORPG to be.

I want to emphasize that I’m going to be looking at console MMORPG’s, specifically. A straight-up massive multiplayer online experience is easy to deliver on consoles: MAG did it way back in 2010 (RIP), for example, and I don’t doubt that Planetside 2 will be fantastic on the PS4. But I think that distinction between “merely” an MMO and an MMORPG is a good place to kick things off.

I won’t go so far as to say that the role-playing experience is such a core feature of your standard MMORPG that it acts as these game’s primary draw: generally the percentage of gamer’s who actually role-play in a RPG is low, compared to the people who are there for the gameplay/community/pvp itself. But there’s one feature of an MMORPG that’s unique to an MMORPG that’s lacking in a standard MMO: individual distinction. Let’s take Planetside 2 as an example: in that game, the only person with any real distinction in your mind is yourself. But zoom out, looking at all the people around you, it’s pretty much impossible to distinguish anyone from each other outside broad strokes of who’s your friend and who’s your enemy. And that’s ok, because in a standard MMO the other players are effectively just surrogates for AI: intelligent, responsive enemies that make the game challenging and rewarding.

That’s not the case in a MMORPG. Scroll out, look around, you see countless individuals with different faces, wearing different armors and different costumes, different titles hanging over their heads, pets following them around, unique mounts to ride… some wearing stuff solely because it has the best stats, while others like to advertise the rarity of their equipment, and others just want to look good. Your avatar is unique and reflects your uniqueness, and the fantasy of advertising that uniqueness can be harder to deliver on a console.

Why? Because of communication.

That’s a very broad criticism to lay down on a console MMORPG, but it’s also not unfair. On a very literal level, for one, unless you have a really big high-definition TV (and not every gamer does) it can be difficult to see all those unique, cool costumes everyone around you is wearing. Additionally, since you might not have a laptop on you, you won’t be able to appreciate some of the things you see other players have, as you won’t be able to research it; while you can always count on a player on a internet-enabled computer to do that kind of research for a standard PC MMORPG. When I saw players on World of Warcraft riding on motorcycles, for example, I didn’t appreciate how expensive those were until I looked it up on the wiki. That’s half the reason people play a MMORPG, to brag and show stuff off. If you can’t communicate your feats you may as well play Skyrim.

But communicating uniqueness goes beyond the simple recognition of someone’s styles; it also enters the very literal realm of communicating with fellow players. An MMORPG lives and dies on its community, they are the most important piece of content that the game is prepared to deliver to prospective players, and the fact that it can be a huge pain to do something as simple as typing to a friend over an in-game chatbox in a console MMO is oftentimes the most intolerable aspect. That’s what killed DC Universe Online for me and many others—sure, it was irritating to spend 10 minutes customizing your character’s outfit only for it to be immediately replaced with your standard level-one armor set, but the fact that the chat window had been so small that I couldn’t even see what was on it with my face pushed up against the screen made it simply not worth the effort.

Unless each console version of The Elder Scrolls Online is released with a compatible UBS keypad and mouse, I honestly don’t see how they’d work around that particular problem. Back when Guild Wars 2 was being considered for a console port, one of my first concerns was how Guild Wars 2 has one of the best communities in the MMORPG world, and we wouldn’t be able to appreciate their kindness (or their… unusual fashion sense) on a TV quite the same way we can on consoles.

The gameplay will still be fun, though, for what it’s worth. But people generally don’t play an MMORPG just for the gameplay: by and large it’s shallower than what a single-player game can offer.

Speaking of gameplay, that’s the second largest bugbear console MMORPG’s have to contend with. You look at World of Warcraft, you look at Age of Conan, heck, look at Dungeons and Dragons Online—by the time you’re high level, or even just at the midgame, you have a butt-ton of combat abilities that practically necessitates the use of a keypad. Console MMORPG’s have worked around that problem a number of ways: Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn allows you to shift between different maps of your directional pad, while DC Universe Online uses a combo system as well as liberal use of the shoulder buttons. But these, while functional, are not intuitive in a lot of respects, and wrestling with the controller is more frustrating combat than any game could offer.

Elder Scroll’s Online weapon system will probably make combat manageable when it makes the jump, meaning it too won’t have to worry too much about combat, but it does make the THIRD problem all the more exasperated.

Menus.

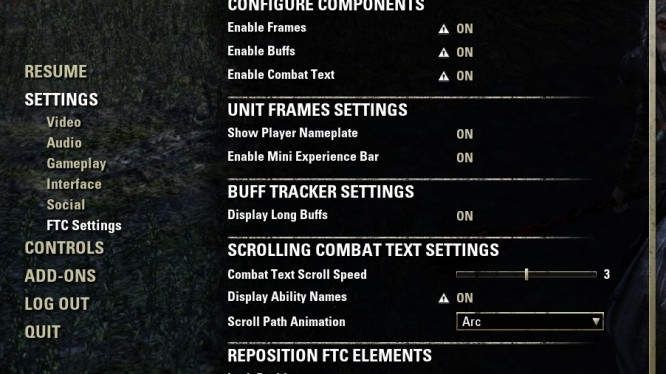

Getting through and navigating menus is a hassle on consoles, even for single-player games, and it’s something that’s always been easier on the PC thanks to the use of hotkeys and a mouse. And now consider how many more menu’s an MMORPG has compared to your standard console title: you have your character menu, your inventory, your maps and your skill selection, your chat windows and your settings and guild menus and the in-game store and the auction house/marketplace, PvP browsers, crafting menus, quest menu, party menus and dungeon menus… it’s an inconvenience on a PC, but on a console that can slow game time to a crawl. This problem will be even more exasperated with the “slots” of Elder Scrolls Online, where if you want to change an ability or weapon you’ll have to scroll through them all with an analog stick. So if you find yourself about to face an enemy you could really stand to swap out one of your abilities for, you’ll have a good minute’s wait to navigate all the menus to switch things around… which can really kill immersion.

So with all these problems, is a good console MMORPG impossible? No, not by a longshot. Like I said, from a gameplay perspective, Elder Scrolls Online will probably be perfectly functional. But as I also said, people don’t play MMORPG’s for the gameplay alone, generally—they do it for the immersion and the feeling of a living world that can only be delivered with the presence of real people who can easily communicate both their accomplishments (therefore showing off all the things the observer could ALSO do—think of armor/mounts/pets as a travel log you wear) and their distinctiveness to one another.

So to do a console MMORPG right, you have to find a way to help deliver those feelings, hopefully in a way more sophisticated than just packaging each copy with a UBS mouse and keyboard. And that’s where the Kinect comes in.

Look, I’m not a huge fan of the mandatory Kinect for the Xbox One either—I was thrilled to find they were finally releasing a Kinect-free version. But in so far as helping players communicate, it might be just the thing we need, especially if the software can be refined to allow easy voice-to-text conversion. The Kinect, or a system like it, could also make navigating menus easier with voice or gesture commands for opening or closing some windows (thus freeing up more buttons for playing—and possibly playing while navigating a menu, which would currently be impossible on a console). Or, a good console MMORPG might want to take a cue from the Wii U, of all things: a second screen for menus and chat windows could leave the main screen uncluttered and, again, allow for simultaneous play and menu navigation. An app for an iPad that linked up to your game session, for example, would do the job well—sure, looking at another screen to see chat would be inconvenient, but it’s a step in the right direction.

Voice chat is also an obvious solution, at least so far as communication with other players, but to call voice chat better or even equivocal to a chat window is incorrect (at least in my mind), and while it would be good for dungeons or parties or PvP, when it comes to world chat or even just local conversation it would probably be more inconvenient and clustered than it’s worth.

The Elder Scrolls Online for consoles is set to release late 2014 or early 2015, and currently not much is known about how it plans to tackle the above problems, outside a statement back on May 8th saying “We continue to work on the console versions of ESO, and game development has been progressing steadily, but we are still working to solve a series of unique problems specific to those platforms”. The solutions they come up with (and the problems they find) will probably be vastly different from what I’m suggesting, and I hope that they work.

But I’m not holding my breath.

The Mighty Quest for Epic Loot: Upgrading Castle Buildings

The Mighty Quest for Epic Loot: Upgrading Castle Buildings Games Like: DayZ .

Games Like: DayZ . WoW Wednesday: Time is Money, Friend .

WoW Wednesday: Time is Money, Friend . Top MMO Expansions of 2015

Top MMO Expansions of 2015 World of Warships: Destroyer, Battleship, Cruiser - Class Overview

World of Warships: Destroyer, Battleship, Cruiser - Class Overview