It has been an incredible summer so far. For those keeping tabs, I finally finished my last E3 2015 preview/article last week. A handful of pieces can be found here, and several can be found in (WARNING: shameless plug) the latest issue of GameOn Magazine. In the past couple months, I have also become a part-time editor/content manager for MMOGames, editing columns and writing news. Most of my weekdays are now spent researching, revising, and filling the site with fresh content. But I am glad to finally come home to MOBA Monday. I started this column last year, and it’s a sweet homecoming to finally return to it.

Since I started MOBA Monday, MOBAs and eSports have taken off. Since this column began, SMITE has become a top-tier eSport. The 2015 SMITE World Championship featured a prize pool of over $2.6 million USD, and Hi-Rez has since partnered with Microsoft to make SMITE the premiere MOBA on the Xbox One. Blizzard finally launched Heroes of the Storm. Their Heroes of the Dorm tournament (in which MMOGames writer Nick Shively participated) was featured on ESPN2. DotA 2 has outdone itself again, between DotA 2 Reborn placing the power of gameplay back into the players’ hands and The 2015 International prize pool setting a new record for eSports prizes ($16,990,052 USD as of this post). And League of Legends is the biggest video game in the world, continuing to steamroll streaming viewership and simultaneous player records.

eSports have become sports in the last 12 months.

eSports itself has grown exponentially since this time last year, too. In the last 12 months, eSports has become a multi-billion dollar industry. Broadcasts and tournaments have become prime advertising spaces for hardware and software companies, and safe, legal betting companies like Unikrn have arisen, giving further legitimacy to the growing gaming phenomenon. Last month, ESPN Magazine released a special eSports issue, in which the company celebrated the rapid growth of competitive video games.

But there is one thing that has not changed since I started this column late last year. MOBAs have been notorious for their toxic communities. If anything, the collective attitude of online gamers seems to have gotten worse since eSports took off. I have become hesitant to play pickup games of certain titles lately. A casual League of Legends game, for example, is rarely fun anymore. Mean-spirited players criticising other players’ builds and in-game decisions have gotten out-of-hand. For the genre to continue to advance and develop, games need to minimize bad behavior. But is a better in-game environment the developers’ responsibility or the gamers’? Or both?

(NOTE: A lot of games have toxic communities. SMITE’s community–a group I work with almost exclusively–has grown notorious in the last twelve months. But for the sake of brevity, I am going to focus on League of Legends in this article. It is the biggest MOBA in the world. As a result, more psychological research and study has been devoted to it. An article that covers every major eSport would run about 5,000 words, and I have neither the time nor the patience to write something that long. I doubt anyone would care to read it, either. So League of Legends players, I’m not picking on you. I promise.)

“Toxic” is a word I hear a lot these days, but I’m not sure a lot of players truly understand what it means. Yesterday, I played a League game in which my ADC called the bottom lane “toxic;” we were behind in gold and experience. In another game (also yesterday), a player described the other team’s brilliant team fighting skills as “toxic.” Both of these uses are wrong, and they make light of abusive gameplay.

A “toxic” match is a game in which players with poor attitudes harass other players, leave the game (“rage quit” or “AFK”), or intentionally lose. Any gameplay experience in which players maliciously prohibit other players from enjoying the game is “toxic.” Players that use homophobic, sexist, or racist language with ill intent are also “toxic.” Such behavior is inexcusable.

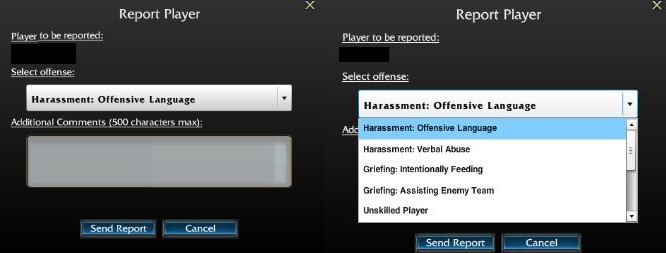

League of Legends, specifically, has taken several steps to end bad behavior. For starters, they have implemented an in-house player report system. Players that have been harassed or bullied can file reports with Riot that take immediate action against malicious players. Reporting players are asked to fill out a short questionnaire. The questionnaire is then filed, the match is reviewed by a bot, and offending players are punished. Punishments range in severeness, from lower priority queues to bans.

Likewise, players can also honor exceptionally benevolent players. Though Riot is still processing long-term honor rewards, they have already distributed several short-term rewards in the last few months. Millions have received free Champions and skins this year for good behaviour.

But maybe the report/honor system isn’t enough. In a news piece I posted earlier this month, I mentioned Riot’s in-house psychologist Jeffrey Lin and his latest findings on long-term toxicity. In a post Lin submitted to <re/code>, he discussed the self-perpetuating problem of the reports system. He wrote:

Our team found that if you classified online citizens from negative to positive, the vast majority of negative behavior (which ranges from trash talk to non-extreme but still generally offensive language) did not originate from the persistently negative online citizens; in fact, 87 percent of online toxicity came from the neutral and positive citizens just having a bad day here or there.

Given this finding, the team realized that pairing negative players against each other only creates a downward spiral of escalated negative behaviors. The answer had to be community-wide reform of cultural norms. We had to change how people thought about online society and change their expectations of what was acceptable.

The findings answered little; instead, they led Lin and his team to another question: “How do you introduce structure and governance into a society that didn’t have one before?” Video games (or the Internet in general) thrive in anonymity. The Internet creates a sense of invulnerability; people do and say things they would never do or say in the real world. If a person gets in trouble, they are banned. If they get banned, they create a new account and continue their mischief. In short, people hide behind fake names to terrorize people in a “fake world.”

But such attitudes have led to real-world criminal mischief. In May, a 17-year-old Canadian was charged and convicted of 23 counts of extortion, public mischief, and criminal harassment for swatting streamers’ homes, stealing their identities, and ordering pizzas with their parents’ credit cards. Last week, Daybreak Games CEO John Smedley declared war on Finnish hacker Julius ‘zeekill’ Kivimaki and his group Lizard Squad, who allegedly grounded one of Smedley’s flights and terrorized his family. Lizard Squad is responsible for last Christmas’ Xbox Live and Playstation Network crashes. Most recently, they attacked Daybreak Games directly by temporarily downing servers.

So how do developers like Riot fix online negativity? The report system isn’t working the way they intended, leading normal players to adopt negative behaviors and creating a self-perpetuating downward spiral of toxicity. And Riot has said on several occasions that they will not remove player anonymity in League of Legends. Banning players is not a viable solution, since users can override their punishments by creating new accounts. So what can they do to remedy the problem? Is it even their duty to fix the problem? And at what point does Riot stop functioning as a video game developer/publisher and start playing Internet police?

Maybe we, the gamers, are the solution. The Internet is still very wild, but it doesn’t mean we should act uncivilized. If we start playing games the way we want them played–by having positive attitudes and shutting down abusive players and bullies–the games themselves will change. If we stop using offensive language, we will eventually stop hearing it (or reading it). Developers like Riot can only give us the tools to enact change. We must be the catalysts. The developers have done most of the heavy lifting; we need to meet them in the middle.

Source: <re/code>

Shadow Realms: MwaHaHa .

Shadow Realms: MwaHaHa . Rift: Quick Guide to Loyalty Points

Rift: Quick Guide to Loyalty Points Plants vs. Zombies 2: How to Survive Level 30 of The Lost City

Plants vs. Zombies 2: How to Survive Level 30 of The Lost City Top 5 Horror MMOs .

Top 5 Horror MMOs . How to get House of Wolves Gear early in Destiny

How to get House of Wolves Gear early in Destiny