The female version of Mass Effect's protagonist Commander Shepard, colloquially referred to as “FemShep”, has become something of a rallying figure for gamers starved for strong female characters in an age of dudebro mainstream protagonists. For me, FemShep has become more than that; it has become something personal, something deeply affecting. For me, it has become an eerie parallel to my mother’s life throughout the series—both Shepard’s triumphs, and her failures.

Now that the Commander Shepard arc has ended with Mass Effect 3, I’ve set out to try and understand why it’s been so difficult for me to say goodbye to the series, and to learn how FemShep succeeds where so many other female video game characters have failed.

I was raised in a single-parent household by a woman who had—let's go with an "unhealthy fixation" with science fiction. We watched Star Trek, Star Wars, Stargate and various other star-themed bits while I was growing up. For her, I think, science fiction provided both a realm in which to escape and a hope for a better future. That vision became a mentality that she not only passed on to me, but one that she carried with her and made every attempt to embody in her job as a social worker.

I was raised in a single-parent household by a woman who had—let's go with an "unhealthy fixation" with science fiction. We watched Star Trek, Star Wars, Stargate and various other star-themed bits while I was growing up. For her, I think, science fiction provided both a realm in which to escape and a hope for a better future. That vision became a mentality that she not only passed on to me, but one that she carried with her and made every attempt to embody in her job as a social worker.

I noticed early in life that my mom dedicated herself to helping others. She helped rehabilitate kids in juvenile hall and she helped people who were disabled and unable to work find the programs they needed to get by. For several years, my mom would organize toy and food drives and then we would deliver what we could on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day to local shelters.

She told me that as much as she wanted the world of Star Trek to exist now, we would never get there if there weren't people in the trenches making it happen. She made me listen to voicemails from people she had helped. "This. This is what it’s about,” she would say. “This is why it's important. This means something to someone. It may seem small, but everything you do, every single thing can be used to help real people."

As a kid it was hard for me to understand what all of that really meant. It was hard for me to grasp why someone would take time to help others. I knew what she was saying, and what she was trying to do, but it took me a long time to really internalize those messages.

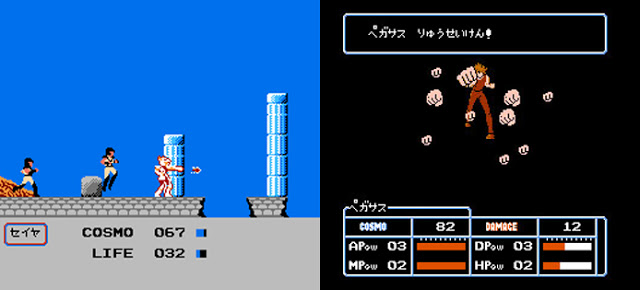

Most of you probably remember Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic as one of the better titles the original Xbox. I, however, saw it as the natural extrapolation of my mom's obsession into the realm of interactive entertainment. After I got her started on the game, she got a second TV and Xbox just so she could play while watching the SciFi Channel. I think all-told, she put more than 1,000 hours into the game.

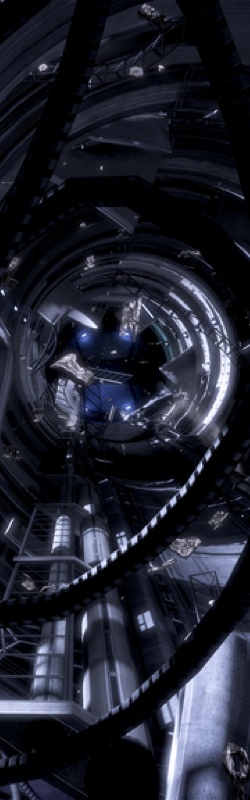

When Mass Effect was first announced, just two years later, my mom and I started talking about possibly going half-in on an Xbox 360. In some developer diaries which, to this day I haven't been able to find again, the dev team said that they wanted to create a modern reinterpretation of a classic 1970s and 80s science fiction film. Naturally she and I both flipped our shit and the deal was sealed.

After almost two years of delays, Mass Effect finally arrived in November of 2007. I sold a stack of games and some Pokémon cards to put forth my portion, and my mom cut me a check so we could drop down the $350 for a Premium Xbox 360 and the $60 for the game itself.

That was two days before Thanksgiving and one week before she was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, an autoimmune disorder that steadily begins reducing functionality of the joints—a big problem for a gamer.

Her condition had actually progressed pretty far by that time, and was paired with another autoimmune disorder—Lupus. She had been able to play Knights of the Old Republic and a few other Bioware games specifically because they were turn-based and slow-paced. Mass Effect, however, was a shooter. It required much faster reactions, as well as precise aiming.

After waiting for two years, she simply couldn't play it.

Despite her diagnosis, I wanted to have my mom with me, even if she couldn't experience the game in quite the same way. Instead, I began modeling my version of Commander Shepard after my mother. I gave her the same sense of altruism, of dedication and of hope for a better future. She gave second chances and she was uncompromising in her pursuit of her pro-social ideals, in spite of her sordid past.

When given the option, I chose to give her a rebellious streak, one marred with “bad” decisions while recalling tales of my mom’s alleged party prowess. I thought an altruistic background would also be a good fit given my mom’s nature. I made her an Adept class, because I think if asked the quintessential late-night nerd question regarding what super power she would pick, she’d opt for whatever got her closest to being a Jedi.

Naming her wasn’t too difficult either. Ever since I was about six years old my mom and I had been watching the Stargate series and its two spin-offs, Atlantis and Universe. Of those, Mom identified with Elizabeth Weir—a civilian commanding officer in the Atlantis series. It fit pretty well too, because she still ships Weir and John Shepard—another character from Atlantis.

Naming her wasn’t too difficult either. Ever since I was about six years old my mom and I had been watching the Stargate series and its two spin-offs, Atlantis and Universe. Of those, Mom identified with Elizabeth Weir—a civilian commanding officer in the Atlantis series. It fit pretty well too, because she still ships Weir and John Shepard—another character from Atlantis.

Elizabeth Shepard. Adept. Earthborn War Hero.

Yeah, that fits.

Shepard is, in a sense, a "walled garden" character. Players are given a framework within which they can craft any number of diverse characters. She can be a Mary Sue, she can be petty or she can represent someone we love. BioWare backed the Mass Effect protagonist with strong writing and an even stronger voice actress regardless of the choices made by the player.

The beauty of the character as an idea and why she has so many rabid fans is specifically because we are free to construct our version of FemShep, complete with all the flaws and facets that real people have. If your Shepard is boring and flat as a character in her development and motivations, you have no one to blame but yourself. If she's complex and consistent, then it is because BioWare has facilitated that construction.

In time, they became intrinsically linked, across all three titles, as I carried Shepard through her journey; my FemShep was a digital representation of my mom. Every major decision helped me empathize with her and understand how her background influenced her values and ultimately her own real-world choices.

The issue with female characters in gaming rarely has anything to do with their "strength" in the traditional sense. Bayonetta is no more a "strong" character than Alyx Vance. No, it's about authenticity. It's about relatability. I've been starved for decently written women in games. Growing up with a single mother, much of my life is informed by that perspective. I've had many women in my life that I've cared for but I can count on one hand the number of times I've felt anything for a female character in interactive media.

The characters in media which resonate with us the most will always be those that represent our own personal struggles, our demons. Through media we can challenge and begin to face our own problems and experiences. The vast majority of games, right now, only offer those opportunities to a minority of people: straight white males. That shouldn't be news to anyone who even casually follows the gaming industry. The fanatical devotion to FemShep, however, is.

I know that, for my part, I made fun of my (mostly guy) friends when, out of some arbitrary desire to be as masculine as possible, they went straight for the male Shepard. I'd ask silly things like "When did they add BroShep? That's new...", always suggesting that not only were they making the wrong choice, but expressing surprise that it even existed (sorry Mark Meer!).

“It’s a boring choice, though. Everyone’s a grizzled space marine these days.”

What made Star Trek—especially the first television series—so incredible was its vision of the future. In it they showed people of various races and national origins as well as men and women getting along, treating one another as equals. It was a stark contrast to every other film and show that was available at the time.

In this century however, our society was still struggling. It took my mom far longer to receive disability than she expected. In my senior year of high school, we had no money coming in. Initially, many of her coworkers donated their sick days. They kept it up for as long as they had days left to donate, but those ran out eventually. We were still more or less okay though. Some family and friends donated what they could to help us along and, in the meantime, I got the financial aid I needed to move a thousand miles away and go to college in Minneapolis.

It is around this time that I started noticing some more parallels between my mom and Lizzy (sometimes she likes to cut loose) Shepard. She couldn’t work, at least not in the traditional sense, anymore. That didn’t mean, however, that she didn’t still have people to help. I still needed her.

That August something happened. I learned that someone else very important to me had stage 4 cancer. My mom told me that morning, and she thought I was going to be okay. I was—for the most part. I went to work and then I went out to dinner with friends. After they’d all left and gone to sleep though, the weight of it hit me. I fell apart like a child learning for the first time that the world isn’t really fair. I texted her, told her that I wasn’t okay. In the next 30 seconds she called me.

Throughout Mass Effect 2 I was asked to gather, steadily, a team that would support Shepard and help her carry out her mission. Ostensibly, the mission was suicidal—something that no one had ever done or could ever be expected survive. Until the end, what exactly the mission entails wasn’t known. How your choices might affect the outcome of the mission wasn’t clearly stated either. I was blind, to a degree, having only my understanding of how my mom would carry herself. That proved to be more than enough.

As I mentioned before, when mom was having trouble getting her application for social security disability approved, about two dozen friends and family members helped us out. At the time I had a weird existential crisis of sorts. I came to realize that there are very, very few who had the same kind of support network that she did. I wondered how our lives might have been different if she hadn’t been as kind and as dedicated and as assiduous as she was.

I was visiting my home state of Oklahoma during the semester break. It was the first time I’d seen my mom in almost a year. She was tired. She wore her stress and anxiety well, but it was still there. Carved into her face, echoed in her voice.

I was visiting my home state of Oklahoma during the semester break. It was the first time I’d seen my mom in almost a year. She was tired. She wore her stress and anxiety well, but it was still there. Carved into her face, echoed in her voice.

She’d been helping out some of the people that had helped us four years prior. Returning the favor, as these things go. Still she was undergoing chemo treatments, and was on steroids to suppress her immune system. They’d certainly taken their toll. She was okay though. She was making it. Pulling through like she always had.

Then, a couple of days after Christmas, a cat that we rescued from a negligent acquaintance eight years ago stopped eating. We had to force feed the cat, Patch, and dribble water in her mouth to keep her going. My mom was taking it really hard. The straw that broke the camel’s back as it were. We took Patch to a vet at the next opportunity. Her liver and kidneys were shutting down. There wasn’t anything they could do.

Two months later Mass Effect 3, the final chapter in Elizabeth Shepard’s story, was released. I was in San Francisco for the Game Developer’s Conference the day it dropped, but at home I had everything set up and ready to go for an epic marathon as soon as I got back, because after GDC I had a week off for spring break.

I kept myself on full black-out for Mass Effect the week of GDC. If someone mentioned it, I walked off. I refused to read anything on the internet. I stopped checking Facebook and Twitter. I was not going to be spoiled. I had no idea the ending was causing as much controversy as it was, and I was able to go in with a more or less clean slate.

I didn’t get what I expected. I won’t let this turn into another Mass Effect 3 ending rant (I already wrote one), but the entire experience left me with a lot of complex thoughts that have taken me a few months to work out.

When I finished the final game, I didn’t want to think about it. I didn’t really want to talk about it much. I needed time to figure out why I felt the way I did and why this ending in particular was so hard for me to really understand. I think I got it now, though. Finally.

See, as positive as I tend to be, I’m also very realistic. Through my experiences at college (yay graduating with a liberal arts degree!), I came to realize that as much weight as our society puts on altruistic behavior, it can be destructive. Shepard was, after all, only a person; an incredibly tenacious woman that rose to meet every challenge with full force, but a person nonetheless.

There was a lot of debate as to the significance of one scene in particular in the Mass Effect 3 opening. Shepard is forced to leave Earth behind, forced to accept that there will be some loss in her journey while also realizing that as painful as that loss is, she needs to fulfill her ultimate goal. She needs to finish the mission.

As Shepard is seen leaving Earth, she turns back to see a child killed by a Reaper weapon and the subsequent explosion. In itself, the scene isn’t really that powerful. The child is given no emotional connection to the audience. We have no reason to care about his death versus the countless millions across the globe. It’s just one small voice in a sea of tragedy. Shepard knows this. She acknowledges it. She understands that its war, the ultimate war, and that people will naturally die.

Still, that child begins to represent all of her failures up to that point. Her complete lack of agency in that moment in spite of all the work that she’s done and all of the sacrifices she has made. She could do so much good, but she was powerless to save one, small child.

Remind you of someone?

My mom too, was no stranger to death. She was an emotional rock. I’ve known her to personally comfort and stay with several people on their deathbeds. Making sure they were in a good place when they went. As much as we loved Patch, as long as we had her in the family, she was still a cat. Not even my mom’s cat really (she had another named Sheba). Still, I’d never seen her react to a death—any death—in quite the same way.

Mom felt helpless, utterly helpless in that situation. All that she’d done before had no value right there. Patch was not a person that could understand mortality. Patch had no way to come to terms with it. No way to accept it. Patch just suffered, needlessly. And my mom couldn’t do anything.

The child’s death becomes a key plot point in the game. Shepard has nightmares about it, and for the first time since Mass Effect I see her shaken – truly shaken – by events outside of my own control. Shepard pushes on though, because that’s who she is, and that’s what she does.

Throughout the rest of the game, several party members from previous titles die in rather dramatic fashion. Each of their circumstances is built up around the consequences of all of the choices I had made up to that point. Not everything Elizabeth Shepard sacrifices is worth it though; some of them result in complex scenarios with subtle and not necessarily complete resolutions. The various branches and paths taken over the course of the trilogy begin to come together, steadily to form a coherent idea – Shepard will have to give up everything to succeed and in the end Shepard may only have a Pyrrhic victory.

Throughout the rest of the game, several party members from previous titles die in rather dramatic fashion. Each of their circumstances is built up around the consequences of all of the choices I had made up to that point. Not everything Elizabeth Shepard sacrifices is worth it though; some of them result in complex scenarios with subtle and not necessarily complete resolutions. The various branches and paths taken over the course of the trilogy begin to come together, steadily to form a coherent idea – Shepard will have to give up everything to succeed and in the end Shepard may only have a Pyrrhic victory.

As great as my mom is, she’s not perfect. Not by a long shot. She has flaws, just like everyone else. When I tried to model her example perfectly in my own life, I lost track of my own personality. I lost myself. I learned that when you spend all of your time living for others, when you dedicate everything you have to those around you, when you fill yourself with the selfless, agapic love of an altruist, some element of your being has to suffer.

My mom tried to never show weakness. She tried to suppress her own humanity so that she could be an unflinching symbol of perfection. I didn’t figure this out until I was past 20. I didn’t understand how little of herself she still had until I tried to live that life—however briefly – and burned myself out in a matter of months.

Shepard was burning out too. She’d been resolute and she’d been unyielding, but you can only wear that mask for so long. The game was drawing to a close, and I knew how it was going to end. I knew what was going to happen.

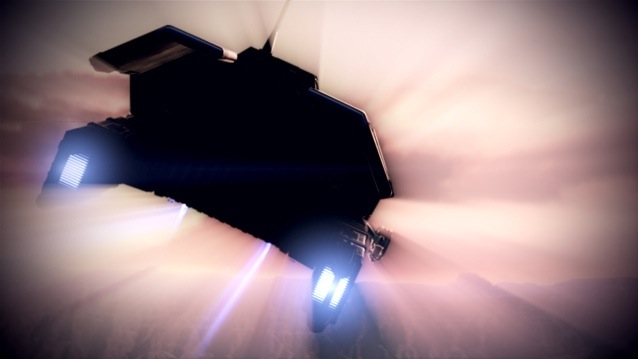

With the remnants of the galactic military and a weapon of unknown origin, she prepares for the final assault. It is the final attempt to reclaim Earth and save whoever is left.

The battle – a grand, bombastic conclusion to an epic space opera—is fought to a stalemate. Shepard and the rest of her crew land on the Earth’s surface to complete a final ground push – the kind that tells you it is an excuse for the writers to include one last human-scale dramatic arc.

Again, Shepard pushes on, against insurmountable odds and, as she does, succeeds. She’s wounded, though, and she summons the last of her strength to stand. Over the course of the next few minutes, I watch her limp forwards.

After some trouble and a few more dramatic scenes, she arrives at the end – both figuratively and metaphorically. She meets an ethereal manifestation of the child that died in the first scene. The child tells her that she can make one of three choices.

She can choose to kill the Reapers, destroying them and every other synthetic life form in the galaxy, she can choose to try and control them and risk losing that command, restarting the war all over again or she can choose to fuse the two—synthetic and organic – into a new kind of life.

At this point, I began thinking of Contact, another sci-fi adventure I had taken with my mom as a child. There too an alien chose to appear before a woman in a form that she’d recognize, and there too that woman was told that humans were too immature to fully understand the forces at play. The difference here is that the child gives Shepard a choice; one choice and one chance to try and end the conflict.

Tired and weakened, she chooses to create a new kind of life. A new beginning for the people and the artificial intelligences that are left. In so doing, she had to sacrifice herself.

It was here that I think the potential implications of the manner in which I’d been playing affected me the most. In a sense, I’d just watched my mom, the most important person in the world to me, die to achieve her goal. That reality is disturbingly poignant now.

A few weeks ago, I called one of her best friends and asked if there was anything my mom had been doing that would fall within the realm of “self-destructive behavior”.

“Yeah. She has. She’s been running herself ragged.”

Somehow I thought that’d be the case. She’s been taking care of several people and helping them out when and where she can. A few members of our family have been in out of hospitals recently, and she, as she does, has taken it upon herself to make sure that everyone has the care and the support they need. She makes one hell of a mother, but she’s awful at being a person. So was Elizabeth.

I see now why it was so hard for me to understand why I felt the way I did after Mass Effect 3. I still haven’t played the extra ending DLC and I haven’t touched it all since the first week or so after its release. BioWare’s recent proclamations about the fourth installment have brought a lot of the issues back to the forefront for me.

They gave me one of the most poignant experiences of my life. I’ve used the series to explore my own real-world problems, understand them and come to terms with them. It has given me so much, and helped me understand both myself and my mother so well. And all it took was one decently written female character. Just one. She wasn’t emotionally distant, she wasn’t overly sexualized and she wasn’t either totally helpless or completely invulnerable.

While I’d rather not see another installment in the Mass Effect universe, if there is one, I’d like to see them make the lightning strike twice. Let’s see them devote their energy to creating a range of characters that will allow people to explore the range of sexual, racial, and gender identities. This time though, I want them to drop the grizzled space marine. If one character, if one well written female character can gave me that, I can only imagine what BioWare could potentially give everyone else.

I don’t know where the current real-world situation is headed. There’s a lot of chaos in our lives right now. I don’t think my mom has learned her lesson though. And I don’t think I can convince her. We’ll see. Hopefully our story will have a better ending.

Weird Room Escape Walkthrough

Weird Room Escape Walkthrough Mortal Kombat X Guide: How to Play Ferra and Torr

Mortal Kombat X Guide: How to Play Ferra and Torr 15 Excellent No-Sign Up Websites for Everyday Use

15 Excellent No-Sign Up Websites for Everyday Use Craft The World (PC) tips

Craft The World (PC) tips Destiny: Earth, Old Russia and Cosmodrome Gold Loot Chest locations Walkthrough Guide

Destiny: Earth, Old Russia and Cosmodrome Gold Loot Chest locations Walkthrough Guide