The Playstation 4 has finally been exposed. Sony bit the bullet and began the All-Clown Circus of the Next Gen Hype Wars. It was a dull affair at best, feeling rather oddly like a repeat of the PS3 launch, only with the word ‘Social’ crammed into every available crevice. Undoubtedly we will soon have a similar show from Microsoft, only with more retchworthy ‘Aspirational Lifestyle’ videos of happy families bowing to the ad altar of Xbox.

I didn’t watch the unveiling live, choosing instead to play some games with friends, and so I had been catching up with the event through various sites when a friend linked me to this article from The Gameological Society: The most striking part being this section on David Cage’s presentation:

“If Blow was a high point, his follow-up act—Heavy Rain creator David Cage—provided a counterbalance. “When people ask me what feature I want in future consoles, my answer is always the same: emotion,” Cage said. (Never mind that “emotion” was explicitly advertised as a feature of the PlayStation 2—the PlayStation 2 is old, and therefore it is a shitbox of lies.) He then launched into a cretinous analysis of media history. Cage asked us to consider black-and-white silent films. Their images were indistinct, Cage noted, and the actors had to exaggerate their actions. These films struggled to convey emotion because the technology was just too darn limited. Cage argued that until the PS4, video games have been akin to those old worthless silent movies. But because the new box has a super-fast processor, games will finally be able to convey emotion.

On the big screen behind Cage, he illustrated his points with scenes from Edwin Porter’s 1903 silent film The Great Train Robbery, which is only one of the most important and influential motion pictures ever made. Touring the nation to sellout crowds for years, The Great Train Robbery introduced the concept of cross-cutting—in which the action on screen cuts back and forth between two scenes taking place at the same time, creating remarkable dramatic tension. So, to recap, Porter expanded the cinematic vocabulary in a way that forever affected the way we perceive moving images, and David Cage saw fit to look down his nose at him.”

Watching the section myself I was blown away by the self-aggrandizing delusion offered up by Cage. Every point made in the Gameological article is absolutely spot on and succinctly shows the level of cinematic ignorance that Cage displays, as such I won’t talk about his statements in relation to cinema overall. Instead let’s look at the incredibly disrespect he offered his fellow game developers.

Cage posits that until now, games didn’t have enough emotion. Apparently a lack of teraflops, polygons and shaders meant we just couldn’t connect with characters! We need the latest technology, the techniques that are used in cinema to create such emotional masterpieces as Transformers: Dark of the Moon. This idea is a complete load of crap and it neatly dismisses the efforts put forth by developers on the supposedly underpowered hardware.

Games, while not often thought of as the bastion of great storytelling, have had great success in eliciting emotion and connecting players to their characters. The power of the machine has very little to do with it; it’s the artistry and craft that does. Just look at an iconic character like Link of the Zelda franchise. In his debut he was little more than a 3-colored sprite with a handful of animations, but players loved him. Nintendo imbued this tiny sprite with a sense of adventure and a cute charm using only a few pixels. Granted, player’s imaginations filled in the gaps, but that was understood by the game’s creators and planned for.

Game developers who understand limitations, like any other artist, are capable of using them to their advantage. One of the best examples is the original Silent Hill from Konami. It’s the tale of a man pulled into a nightmarish town while searching for his daughter; replete with horrors and terrible sense of loneliness. Team Silent built a fully 3D environment for the town that players would wander, one that taxed the PS1’s hardware and required a very short draw distance, so they used this and created a thick, oppressive fog that covered the world. It was a visual, narrative and technological fit, and gave Silent Hill the atmosphere and emotion that the story required. In fact it was so successful that the fog became a trademark visual of the series, so much so that the first film adaptation required a heavy amount of high-tech, post-production alteration to match what had started as a low-tech issue. The film even repurposed the haunting music that was written for the series by Akira Yamaoka, proving further the worth and power of the ‘underpowered’ games.

For a final example let’s look at one of the best written series of the last and current generation: Phoenix Wright. Starting life on the GBA in Japan, a console with roughly the power of a Super Nintendo, the series moved to the DS for its worldwide distribution, a console with roughly the power of an N64. These limitations were absolutely no barrier for Shu Takumi and his team when it came to making brilliant characters and emotionally effective stories. What they used, first and foremost, is incredible writing: the absolute base for creating any good story and any emotion worth having. Before the visuals begin the characters are given their distinct depth, personality and interest. You love them, you laugh at them, you hate them; they evoke every emotion a good story can. Still, being a video game there is a visual component, but it’s a very technologically sparse one. Each character is comprised of a handful of still images and some very, very short animations, but they’re all that’s needed. The developers understand timing and using precise music hits, flashes and quick transitions they bring these characters to life. It’s a technique that was so effective it was carried over to the similarly well-written Ghost Trick: Phantom Detective.

Still if we listen to David Cage none of these represents anything worth thinking about now we’ve got the raw power of the PS4! With a quick wave of a hand he sweeps such wonderful work, such important steps, under the rug and out of sight. It’s a horrible lack of respect, and a dangerous lack of understanding of the artists who came before him and it’s one that has shown in his own games.

Fahrenheit/Indigo Prophecy was a game with lofty ideals and a very high opinion of itself. David “I’m not a frustrated movie director” Cage even introduces the tutorial himself, which is available under the menu option marked “New Movie” and not “New Game”. It pretends to be behind the scenes on a film set, where Cage will guide you through understanding the boldly awkward controls you’ll be using and the idea of QTE’s. These are introduced as if they’re innovations, rather than simply variations on existing systems, which is seems like an indication that he doesn’t think much of other developer’s work.

The story in the game itself is laughable. It begins with a decently interesting premise: A man in some kind of supernatural trance commits a murder against his will and tries to escape the cops while figuring out what has happened to him, but soon the story descends into the weird, unfocused ramblings usually associated with low-budget direct-to-dvd genre movies. There’s a Mayan prophecy, mystical radiation, superpowers, skeleton angels, hobo conspiracies, worldwide disaster, necrophilia and finally a Dragonball Z-style fistfight with the Internet. It’s an absolute mess of a story, one which takes itself deadly seriously and is all the more hilarious because of it.

David Cage seems entirely unaware of what he produces and comes off as a man enamoured by cinema, but thinks himself above it, and above the work of his contemporaries. If he paid any attention he’d see that emotion already exists in games and has since the start, ably working towards the goals he talks about without the need for insane power. He’d also see that there’s a thriving indie scene dedicated to storytelling, with work like Dear Esther, The Stanley Parable and the booming Twine-Powered Choose Your Own Adventure scene.

It’s a sad thing to see such disrespect and lack of vision from a creator whose work is being fuelled by insane amounts of money, when all around him people are doing more, better and for less.

Interview with Carbine Studios: Free-to-Play and the Future of WildStar

Interview with Carbine Studios: Free-to-Play and the Future of WildStar Fallout Shelter Unlimited Weapons, Caps and Outfits Glitch

Fallout Shelter Unlimited Weapons, Caps and Outfits Glitch Xenoblade Chronicles X: Companion - Recruit / Locations

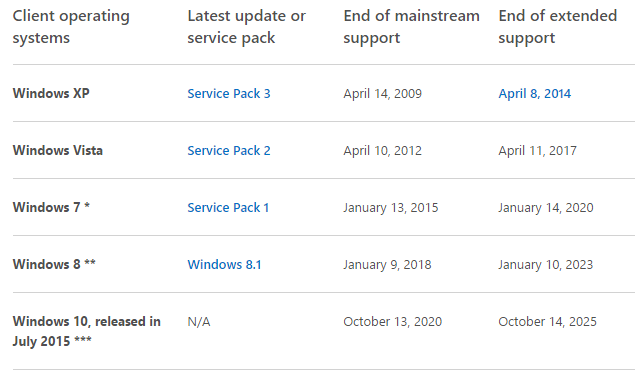

Xenoblade Chronicles X: Companion - Recruit / Locations Why You Need to Upgrade Windows 8 NOW & Your Options

Why You Need to Upgrade Windows 8 NOW & Your Options How to make Unlimited Money in Watch Dogs

How to make Unlimited Money in Watch Dogs